Seddon cafe, Saturday morning. Red car parked nearby. Pure, unadulterated salt. Wild harvested in a collaboration of respect.

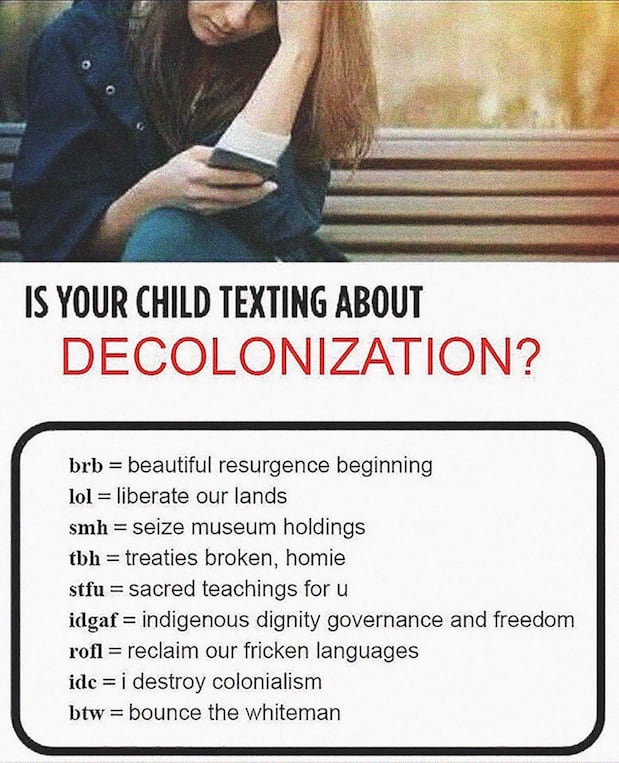

Decolonise your knowledge, decolonise your desire, decolonise your body, decolonise your fashion, decolonise your spice rack, decolonise your gut, decolonise your reading list, decolonise your seating arrangement, decolonise your watch, decolonise your pedagogy, decolonise your arts practice, decolonise your IG account, decolonise your meme.

It starts with colonised peoples talking about their empowerment and, necessarily, it’s a wide open road with Indigenous and non-Indigenous participation. But with these white artworld people in particular ... I am wondering, is it decolonising or re-colonising?

The kind of engagement from non-Indigenous people is different. I feel lately like I’m living in a surreal alternate reality. I see white people wandering the streets in t-shirts that read ‘Decolonise Now’, posting memes about decolonisation on their Instagram pages, and dropping ‘decolonial’ left right and centre in Art World Discourse. Walter Mignolo’s ideas about decolonial aesthetics call upon arts practitioners to understand how colonialism operates at the level of the visual, at the level of taste, and this seems to be how decolonisation has begun to gain so much traction as a buzzword in the arts world. Does representation offer anything to decolonial struggle?

Well, culture is transforming on the reg, it’s not stopping no matter what, so visibility and representations of real intentions and ideas is important. I’m wondering what’s at risk though, what’s easiest for people to consume, to take at the level of metaphor, log off and call it a day.

It’s like how Beth Sometimes and Lorrayne Gorey discuss in their piece in this issue, that it’s easier to talk about language than it is to talk about power. Language is power, and for colonised peoples ‘decolonising the mind’ remains just as important as decolonisation at the level of land, politics, and economics. But then if we keep the focus purely at the level of the visual, linguistic, or aesthetic, we can let ourselves off the hook from talking about the harder stuff; repatriation of lands and waters is harder to think about than putting on a t-shirt.

I had this weird experience when my show Black Magic opened during Midsumma, and someone called it ‘a show about decolonisation’.

I thought your show was about the legacy of Christian morality on Indigenous genders and sexuality?

Yes, the show was about sex, humour and religion. It was supposed to be funny.

I still believe in the transformative potential of activism at the level of culture, but I wonder where these t-shirts and hashtags are going and who they serve. I think this is why I value the discussion of ‘New Aboriginal Kitsch’ in Lauren and Tristen’s piece so much. Are these kinds of ‘decolonial aesthetics’ attempts to resolve some of the more irresolvable parts of illegal, ongoing occupation of Indigenous land?

NL: Yeah. In south-eastern urban environments, how much smoke do we have to cut through to get to the basics of decolonisation that all Indigenous groups in Australia are talking about and calling for: the repatriation of Indigenous life and land. I suppose this is a particularly terrifying thought for white people living in densely populated regions like Melbourne.

MC: Hearing you say that, I’m having a memory of this segment of the news I saw from around the time of the Mabo decision. They showed an aerial view of a suburb of Brisbane from a helicopter, saying something like, ‘if we give them this land, maybe they will come for our houses next!’ We have to have these conversations with non-Indigenous people who want to pick up on this language of decolonisation, diversity, and intersectional feminism, and ask what they are really willing to give up. In the art world specifically, who has the institutional control, the wealth, and the land.

And the cultural materials that connect up history. Contributions like Rene Kulitja’s show that repatriation of materials and memories, even if digital, enrich the health of individual and community lives. And that we are capable of looking after our own goods in our own professional archives, thank you very much Mr. Coloniser! What’s cool is seeing artists at the forefront of these critical discussions and demands, re-distributing powerful meaning between institutions, community and Country.

Genevieve Grieves’ paper ‘Connecting with Wounded Spaces’, and works like Julie Gough’s Lost World series, take a second look at the living archives we walk with everyday. Landscape and place are living sites with so much knowledge to give if people are willing to listen and bear responsibility. Which brings me to the question of what non-Indigenous people in the arts world are really doing with themselves, aside from wearing some t-shirts? And I’m not talking about turning up at Invasion Day protests once a year....

Something I wonder about is the prevalence of collaborative works in the arts world. We have a few co-authored pieces in this issue. In arts practice, collaboration between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people seems to represent more than just sharing the workload. There is an assumption that ‘two-way’ dialogues can be decolonial in and of themselves — that there is a transformative power exchange involved. White people might even assert that they can choose to ‘cede’ authority through mutual dialogue. Again, I’m going back to one of the lines that brought us here in the first place from Tuck and Yang (which is also featured in Kate Rendell’s piece Open Cut), ‘The cultivation of critical consciousness, as if it were the sole activity of decolonization; to allow conscientization to stand in for the more uncomfortable task of relinquishing stolen land.’

Beyond the pleasurable chill, the cathartic, awe-inspiring release of acknowledgement is actual work to do. It’s kind of like losing your virginity, make it fun! We would LOVE some more hands!

But Maddee, here’s my real concern: what’s going to be the next big fad? What happens after this?

Editors sit in uncomfortable silence indefinitely, reggae music increasing in volume................

Maddee Clark is a Yugambeh freelance writer, curator and educator living in Narrm. Maddee’s work has appeared inOverland,NextWave,NITV, Artlink and the collection Colouring the Rainbow: Blak Queer and Trans Perspectives.

Neika Lehman currently lives in Narrm, working as an artist, writer and educator. She descends from the Trawlwoolway peoples of North-East Tasmania.