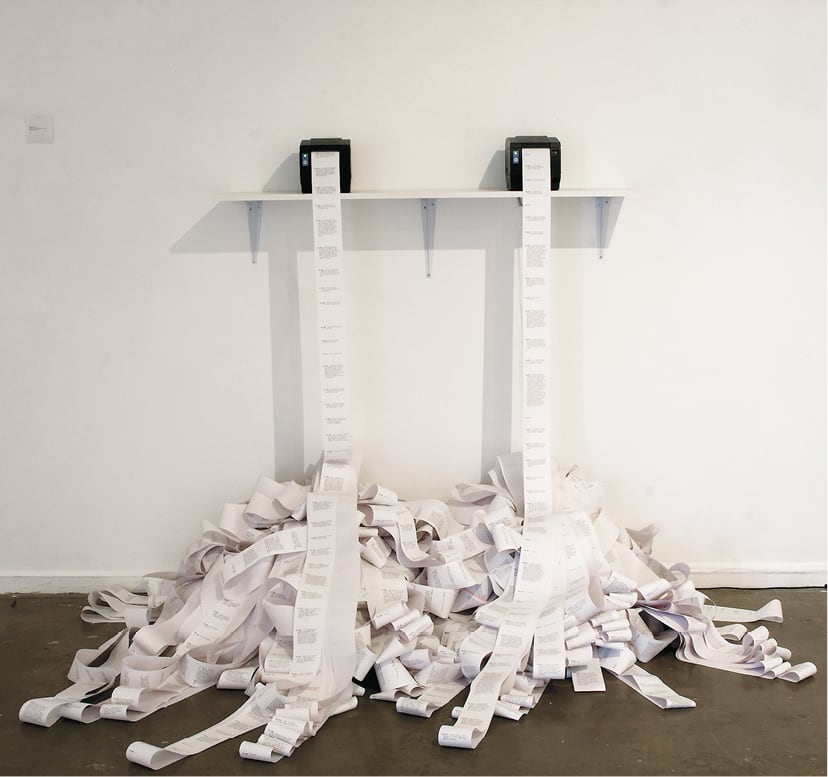

Ben Forster’s practice traces the limits of logic. He uses computers as the basis of his representation of systems of logic and rationality. Yet it is this rationality that Forster employs in his work to highlight the inconsistencies of this system. The young Canberra-based artist has taught a computer how to draw and has programmed receipt dispensers to discuss Marx. His practice, through using computer technologies, attempts to draw out these dialogues.

In April this year Forster began his residency at SymbioticA at the University of Western Australia in Perth. This research centre, one of the only in the world, is an artistic laboratory dedicated to engagement with the living sciences. ‘Bio art’ uses biotechnologies such as genetic engineering, tissue culture and cloning to produce work. First established in 2000, SymbioticA has seen a number of Australian and international artists undertake a residency — most notably, ORLAN and Critical Art Ensemble.

Bio art currently has an awkward relationship to Australian contemporary art. So specialised are the procedures required to produce the work that much of bio art’s dialogue exists within Perth and the well-equipped SymbioticA laboratory. Furthermore, artists are required to navigate fraught ethical territory, given the high risk attached to the materials and procedures peculiar to bio art. Critics have voiced their concern over the funding of bio art exhibitions in the US by biotech firms with a commercial interest in the promotion and normalisation of the technologies of bio art, however, valuable discussion has occurred due to the confronting nature of bio art. The most publicly debated bio artwork is Eduardo Kac’s GFP Bunny (2000), in which, through transgenic manipulations, Kac bred a rabbit that had fluorescent fur and thus glowed green. This work did undoubtedly create intense dialogue globally in relation to transgenic manipulation and the ethical limits of the use of such technology.

Can you draw out the commonalities between your previous work with computers and the work you are planning to do while on your SymbioticA residency?

The common element of my Drawing Machine work and my receipt printers in conversation work is the reduction of something that is quite complex to a logical system, then seeing the inadequacies of that logic. In taking this scientific rationalist view and trying to examine what these things are through this lens, we see that you just can’t do it!

The way your experiments often fail in their rational logic is important to your work…

Incredibly important because it just doesn’t capture the infinite detail of the world, it shows that our logic is ill equipped to deal with the world. I’m going to research extensions of drawing made possible by the emerging technologies of bio art, by biological drawing I mean the act of drawing with biological material.

Could you talk about those plans a bit more specifically?

Basically, I will use parts of living tissue from different things and cultivate them together so they grow into images. I then can film that process of growing and becoming and disappearing. I also want to biopsy myself, take core samples of my flesh from different parts of my body, grow it, cultivate it and put it on paper. I am stretching myself into the multiple — it is ‘I’ as a commodity that can be spread.

Obviously there are ethical considerations surrounding this process.

Every artist that undertakes a residency with SymbioticA has to get ethics approval before they can do anything. So you have to write a proposal in ethicists’ terms, not in artists’ terms. Supposedly, it is really useful for artists to unpick their ideas in a different language. It is a completely different angle from which to view your practice, as something that could be dangerous, and then trying to rationalise it in that way instead of in terms of meaning.

There are potential dangers using biotechnology, you must feel uncomfortable with that…

Absolutely. Disgust and fear are a base emotional response — that biotechnology is a part of our world that we shouldn’t get into. It is almost touching sacred ground.

And yet you do not feel a responsibility to stop?

Yes, I do. But I also think that if you leave it to the scientists it is outside the public’s control. So as an artist I still feel we have a responsibility to question what is going on in those domains. By working with biotech and learning about it, it gives a voice to challenge these issues. At the moment we are just having a base physical response that this is bad but we don’t really know what ‘this’ is.

Do you think is it possible to create work that discusses a range of issues beyond the limits of biotechnology?

Yes, I want to use tissue culturing to explore ideas about drawing. Can a drawing be living? It is obvious that a drawing can exist on living strata, for example tattooing, scarring, etc. We start to think about marks as static things when ultimately marks are fluid. Exploring drawing with biotechnology enables you to really push that point of drawing as this fluid exercise that can live and change. By using a living medium, it is no longer a passive thing that we can manipulate, it manipulates back.

While artists using biotech may want to draw out those ethical dilemmas, do you think there is a danger of presenting the scientist as wonder maker just by the fantastical nature of the work and process?

Yes, there is that tension. With biotech, it begins to conceal so much that you can’t see the processes behind it.

And that kind of awe can be dangerous, for example Eduardo Kac’s fluoro rabbit work. While cautionary, that piece can be seen as a dramatic innovation.

I see that fluoro work as challenging that, saying: ‘why the fuck are we doing this?’

Because the idea of a fluoro bunny is so ridiculous.

And because it is pushing on nature and living things that it should be hitting alarm bells for everyone, ‘whoa, holy fuck what is this?’ This artist is exploiting the technology that scientists are developing — there is this moral crux there.

I guess this is what I’m struggling with, is there a responsibility not to create a sense of amazement? Maybe with that work, it is that shock of what is possible without any kind of restraint. Would you ever consider bio art as legitimising the activities of biotech companies?

From my experience, which is really limited at this point, bio art is about entering into a dialogue with ethics. Basically — is biotech right? This seems to be the fundamental question raised by artists, for example Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr developed a project, Disembodied Cuisine (2003), in which they took a biopsy of an animal that continued to live then, using tissue engineering, grew a semi-living ‘steak’ in the laboratory that they then ate. That to me is the strongest example of bio art not legitimising but undermining biotechnology. But yes, if the work doesn’t quite hit the mark then there is a real danger of glorification.

And SimbioticA is the only lab in Australia that artists have access to. Entering a laboratory for the first time, the biotech process could be hyper-interesting to the artist but from the viewer’s perspective the work could be really banal.

All bio art is performance in the sense that it is living and it changes and it is moving, but it is stale in the sense that it is only residue that people see. The audience is not in the laboratory and they are not seeing it actually happening. I think that this is a major tension for artists using it: trying to get this performative aspect, that is held in a laboratory and that is sanitised, into the public eye, somehow capturing that and pushing it out there, is the challenge.