The cinematic works of the legendary New York filmmaker Jack Smith and the lesser known, but equally important, Brighton based filmmaker Jeff Keen, present us with two highly developed versions of the trash aesthetic. In his oft-cited appreciations of Maria Montez and Josef von Sternberg, Smith rails polemically against the hegemonic naturalism of both Hollywood film and mainstream European ‘art’ cinema. Against the ‘inevitable execution of the conventional pattern of acting’ and the rule of the ‘good story’, Smith posed the ‘visual revelation’ of the ‘neurotic gothic sex-coloured world’ of the B-movies Montez starred in and von Sternberg directed.1 Modern cinema attempts to subjugate the sensual power of the image to the plot and dialogue, but the image is always in excess and reveals itself to be a ‘visual fantasy world’ — autonomous from its narrative purposes.2 Smith’s own films, including, most famously, Flaming Creatures (1962–3), clearly stem from the same aesthetic program as his critical writings, considered by him as a continuation of the ‘never perfected’ art of the silent film — the -rubbish-tip opulence of his set-pieces reaches back to the orientalist Hollywood of the 1930s and 1940s to create a non-narrative cinema of disposable, sensualist kitsch.3

As Branden W. Joseph argues, Jack Smith’s work must be understood in relation to both surrealism’s appropriation of the ‘wish images’ of the immediate past in outmoded commodity and popular-cultural objects, as well as the anti-narrative cinema of the ‘optical mind’ as proposed by Stan Brakhage.4 Jeff Keen’s cinematic works are also best understood in the light of this aesthetic constellation. In works such as Cineblatz (1967) and Rayday Film (1968–1976), the viewer is bombarded with lightning fast stop-motion animations of collaged advertising material and tabloid images, burned and disfigured children’s toys, pornography, reframed television screenshots and double-exposed footage of the director, his family and friends costumed as B-movie archetypes in play-acted fragments. Like Jack Smith’s films, Keen’s work is an exploration of the aesthetic and irrational potential of outmoded popular culture such as B-movies and comic books. In a similar fashion to how Smith’s Flaming Creatures moulds Hollywood orientalist motifs into an excessive series of tableaux vivants, orgies and dance scenes free from narrative, Keen’s Breakout (1962) scrambles the standard events of a film noir into a blur of stereotyped figures which, without narrative causality, take on an abstract quality and reveal themselves as no more than a catalogue of gestures shared with the pulp-fiction books and magazines we see in the film’s opening sequence.

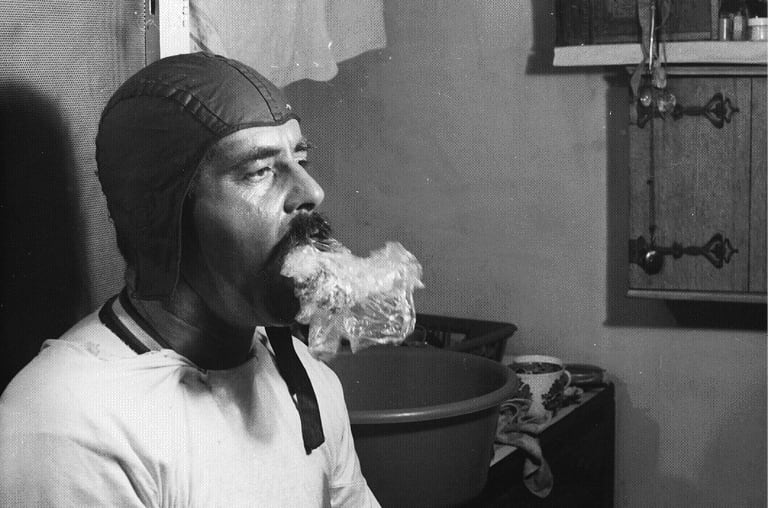

There is a great deal of truth in Susan Sontag’s characterisation of Smith’s work as ‘strictly a treat for the senses’, and we could argue that Keen’s work also operates in a modality starkly opposed to that of the ‘literary film’.5 However, we only begin to understand Smith’s and Keen’s particular take on the opposition to narrative when we see it as inextricable from a general resistance to normative standards of behaviour. Smith’s writings abound with references to his struggle against what he calls the ‘normals’.6 The abject sexuality of his cross-dressing creatures, who tug at one another’s breasts and perpetually flaccid penises, is as clearly directed against normative sexual subjectivity as the hippy-commune utopia of the naked frolicking of Keen’s expanded family and placed in opposition to the stiff-upper lip of the British family unit.

As Smith realised, to appropriate the lowliest popular culture of the immediate past and celebrate its ‘phoniness’ is to ‘hold a mirror to our own’ phoniness and denaturalise the conventions of contemporary cultural production.7 The hammy joyousness with which the ‘actors’ in both Smith’s and Keen’s films adopt their low-brow personas are one brand of evidence for the creative potential of this critical agenda. On a less immediate level, we can see how the rhythms of Smith’s and Keen’s films also bespeak intense critical engagements with mainstream film and television. In Smith’s work, the tight editing and utilitarian framing of Hollywood is replaced with a deliberately amateurish, shaking hand-held camera and excessively long shots. In the final dance scene of Flaming Creatures, as in the earlier Scotch Tape (1959–62), the discontinuity of these amateurishly produced visuals, with the recycled Hollywood music that provides their soundtrack, gives the image an uncanny new life that seems to dramatise the autonomy of the image that Smith had argued for in his writings. Keen’s films, on the other hand, push the paratactic logic of television news and advertising to extremes, especially in the Artwar series he began in the 1990s. The frequent inclusion of television news coverage of war alongside destructive stop motion animations and scenes of Keen dressed as a soldier seems to both critique and fetishise the subliminal tactics of television media through hyperbolic redoubling. Smith and Keen both confront contemporary regimes of representation with repressed and outmoded material. In this confrontation, they open up new potentials for these ‘trash’ materials to find an oppositional aesthetic space of pure imagery and ‘visual revelation’.