Office of Australia

23 January – 20 February, 2010

Box Copy, Brisbane

Joseph Breikers of Boxcopy is also present

How do you see a strategy such as institutional critique functioning within a space like Box Copy?

For me the initial impetus for providing a critique about this small institution was to look at the latent conditions of the gallery space and how these inform engagements with the exhibition.

Do you know what this room was initially used for?

I think it used to be a paint warehouse but then, because it’s obviously been renovated a few times, it was an office space similar to the architect’s office next door. So you get traces of previous occupation from the architraves, the picture rails, the polished timber floor and the glass doors. When I first entered the space during a previous exhibition, I noticed these resonances of its previous use. All the walls had been painted white to turn it into a gallery. Then there was also the awkward positioning of the gallery sitter.

Where would the sitter normally be?

In the exhibition space, over in the corner, behind a narrow white desk.

So they are actually in the exhibition?

Yes, but almost apologetically. There was a sense that their presence was not to interfere with your engagement with the exhibition.

In a way the sitter is pretending to be outside of the exhibition space whilst sitting inside it. Why can’t the attendant sit outside the space in the corridor?

It would be an issue of getting in the way of the other tenants in the building.

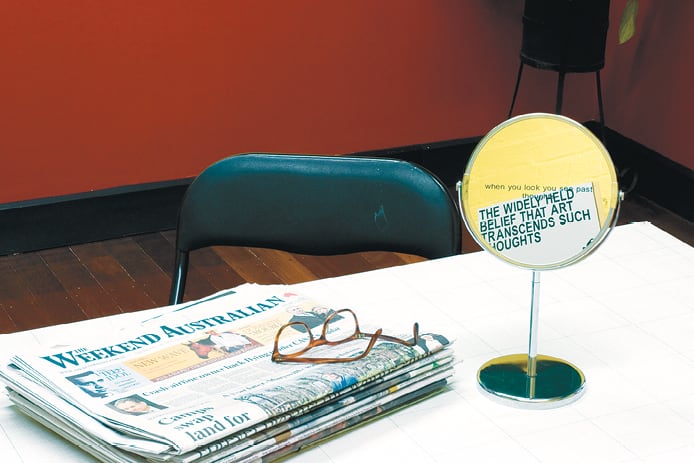

So rather than treat this as a regrettable problem, I sought to look for opportunities that might contribute to how potential visitors engage with art in this context. Having the gallery sitter prominently in the exhibition space automatically sets up the potential for a discussion. There is a three-way scenario that is established between the visitor, the artwork and the gallery attendant. Rather than having a visitor come to look at the work and then leave — perhaps to talk about it elsewhere — the exhibition plays-up the scenario of having a dialogue with a gallery attendant in the context of the work.

Do formal concerns move you towards more political concerns?

Definitely. I think that it can resonate with other ways of thinking about space in relation to politics, like the landscape of a city or the spatial qualities that inform a discernable social group.

Joseph, have you had exhibitions here that have dealt with the space in a similarly geo-political way?

No, this has been the first exhibition that has looked more at the politics, or personal politics of viewing art. I think the other previous exhibitions have responded to the space but in a more site-specific way.

Dirk, why did you then un-make the exhibition space? It’s quite an aggressive action on the white cube. You’ve turned it into a space for political engagements.

Part of the action is looking at what was latent and what was here before the room was painted white. Another part is suggesting that maybe the existing condition wasn’t so problematic, or that it would have sufficed: that, in fact, painting the room white is symptomatic of or perpetuates other strategies for colonising space.

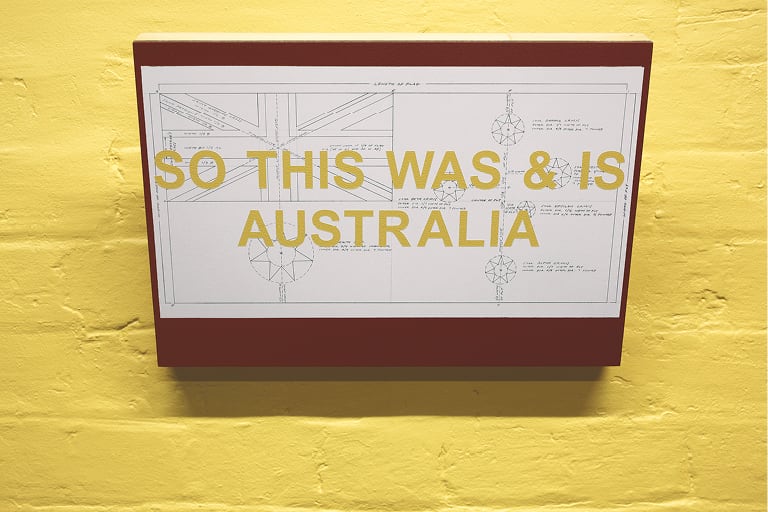

My initial interpretation was that you have overt political approaches to problems of nationalism in the two dimensional works on the walls. These do not seem so latent, they’re quite in your face. There is a tension between the concern you have on a political level — which is quite overt — and the formal installation practice, which is quite subtle.

One way of seeing this space is via the formality of being an office of business. I have tried to ‘undo’ the gallery so that it is not a philosophically separate space to the hallway outside, or the street, or where you live. I have tried to make it similar to other spaces as well as declaring its presence or context in Australia. It is an attempt to set up a landscape against which you see yourself — one that isn’t isolated or autonomous. The political provocations that are on the wall are intended to be things that also have currency in other places, other than where we are. So when, say, Joe’s working on his laptop, maybe writing an email to a friend or writing an essay, these statements about what it is to be Australian, or what it is to not be able to get married if you’re gay or lesbian, inform simultaneous situations that are other than looking at art.

If you have not seen this space in its other life as a white-cube, it may be a very confusing situation. Are you attempting to confuse the visitor?

The colourful walls and the way I have tried to make a social place in front of the work can seem minimal and confuse people as to where the work is. Part of the exhibition is trying to make the work ordinary, rather than being out of out of the ordinary. This is one way to suggest that the work could happen anywhere, it doesn’t have to happen in gallery. It could be in your lounge room or in an accountant’s office down the road. The paintings are a backdrop to the conversations. The work is the actual provocation of discussions that will take place — but even if there isn’t, even if the dialogue’s not about the work, it’s a reminder that these concerns are present.

Maybe the work is the conversation that we’re having right now, as well as all the conversations that have occurred during this exhibition?

That is the intention. I think of the work as an agent.

How do you digest the theatrics of installation practice in your work?

I guess that this kind of strategy is the antithesis of Michael Fried’s Art and Objecthood. I try to develop a situation in which the visitor reads themselves against — as well as considering how other people may read their actions within — such a context. I try to be subtle, to always allow things to happen.

But the reality is that nothing usually happens, so if nothing happens, does it mean it is a very realistic work?

I think that the exhibition has an agency that allows it to function beyond its literal use. It is indicative of other situations outside of the exhibition in which similar dialogues can take place. That’s the way I think about art and particularly painting as being in contexts other than exhibitions. The intention is that it provokes or shadows a discussion, reminds you of an event that changes your next sentence, without necessarily being directly about the painting or whatever’s on the wall.

You’re doing more than reconfiguring or redirecting the space, you’re also manipulating the people, the circumstance within the space. Do you see yourself doing it more overtly in future work?

Yes, I did a previous installation where there was a set of mirrors on one wall and then, on the opposing wall, was the Australian flag. When you were between the two walls, you were caught in the middle of the work — you couldn’t help but see yourself against the backdrop of the flag. I think that was one way to imply your participation in a scene that you’re not necessarily agreeing to be part of. When you think of the Australian flag as an emblem that attempts to represent a group of people who, it is implied, are accepting of it, I think it begins to say something about responsibility and participation. You can either be passive to its functioning — as if it doesn’t affect your experience — or you can work through this construct that obviously has some agency. So I think that’s the path that I am pursuing: the idea of implying participation, falling into something or finding yourself within a scene that you weren’t necessarily consciously partaking in.

In my experience I find that it’s difficult to encourage the audience to participate in the work of art in a more passive way or less passive way. So you’ve got two choices where you have to be relatively explicit almost to the point of having instructions, or setting up a kind of trap — if you like. I really like that, the very sly ways of going about it. Then people are put on their back foot in that engagement with the work, which I think may be more beneficial than being able to prepare while being instructed.