Koorie Heritage Trust, Melbourne, March 2010

Originally, Lyndal Jones’ country house was imported from Europe, more than 150 years ago, and reassembled in the regional Victorian town of Avoca. Jones discovered the property, which had been abandoned and had fallen into disrepair, purchased it and then remodelled it into an artist residence and project site called The Avoca Project.

We spoke to Lyndal Jones about this ongoing project and her recent work with Jill Orr, including Sustainable Fusion Reactions, a collaborative project with artists Utako Shindo, Bindi Cole and Ash Keating. The resulting exhibition was presented by the University of Ballarat Art Academy last October and again in November at the Colour Factory in Melbourne. Together we spoke about some recent projects in the communities of Avoca and Ballarat, which have embodied a complex engagement with issues of dispossession, colonisation, immigration and revolution.

So, Lyndal, how did your association with Avoca begin?

I didn’t start having an association with Avoca — I started having an association with a house that happened to be in Avoca. In the 1950s it was derelict and when I purchased it a few years ago — because it was the only way to do anything with it — the Howard Government was absolutely still in power, and the anti-immigration sentiment was so strong. The house was a pre-fab from Europe, a first generation immigrant. So, as such, it challenged our preconception of home and our ‘Australianness’.

It’s a very rich base to have, a site of transposed European immigration.

It offers people really quite a lot. It’s not just a house but a studio with a workshop and a big garden around it. A lot of the outside work has been done with Mel Ogden, a land artist and he has used a lot of local rocks. And Simon Popley who is a climate change activist and a builder. He has been really instrumental in underpinning it. In the house there were quite a lot of other artists as well. Lily Hibberd did a performance. Kim Donaldson did a video. Les Gatsby did a series of prints. I own a series of etchings from Indigenous women of waterholes and they were also shown throughout the house. Brie Trennery had a video. Katarina Frank made some plates that were beautiful. Terri Bird had a piece, Julie Shiels as well. And also, up at the hall, Gayle Maddigan and Megan Evans had a huge piece where they worked with 80 townspeople on a big video installation, as part of a long-term residency at the house.

How did your involvement with the Avoca Eco Living Festival start?

I just announced to the town business and tourism committee that we were having one! Then I asked if people wanted to join me. We gradually took on other people, but what was interesting was that people were very reluctant to engage with something so amorphous. It’s a community that has been in some pain, particularly between 2008 and 2009, there were five suicides in one year, and there has been again one recently, but it seems to be that in the town — that is a form of response for personal anguish. It seemed to me that if I’m dealing with issues of climate change, it was necessary to somehow engage the town. It’s all very well to engage people who already knew about it or who were already in agreement. Avoca has a population of about 1,000 people. It’s one of the poorest areas in Victoria. There are quite a lot of older people there. Like a lot of these towns, you know you think it’s reviving, then another shop closes down, and another opens up. It’s kind of a borderline community.

So it was quite an organic process of curating the festival, working together and developing ideas and exhibition plans. Was it instigated in reaction to a perceived lack of interest by other curators in Melbourne looking at issues of sustainability and eco-living?

My concern with the whole house is that the difficulty in Australia for artists wishing to work on any kind of issue pertaining to sustainability is that once you’ve had an exhibition, no one is going to want to have an exhibition in the same way again for several years — that idea has been done. It seemed to me that this issue was bigger than just an idea to be done. That’s the purpose of having an ongoing project, so it means that I can keep on working like that and I can bring in a lot of new people.

So where did your initial conversations with Jill start?

I phoned Jill because I had a good relationship with people at the primary school. Jill suggested that she do a residency at the primary school towards what I called the Avoca Eco-Living Festival. If you notice, it doesn’t have the word ‘art’ in it anywhere. So every year there will be an Eco-Living Festival that’s both local but also brings people in. There was a whole range of things, but the point is that it is not to be another one-off. The site is a research site for me and other artists who are interested in a sustainable festival. So it was about finding ways, through the means that we had, to deal with issues of global warming and the school was the most open and receptive place to start.

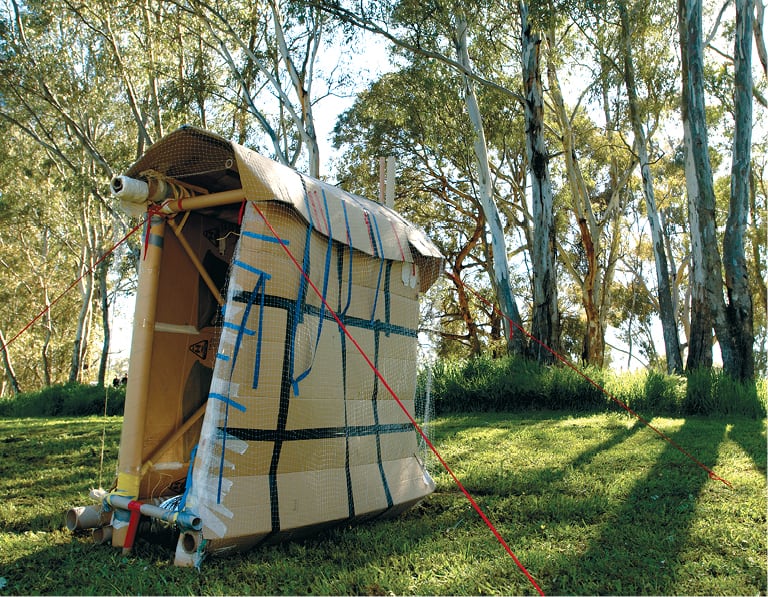

Then I was brought into the picture. What I did with these kids, who were two groups of twenty-five students, with an hour and a half each, was to make sustainable cubby houses. But I can’t really say they were sustainable because they were made from cane and recycled materials, so really they were recycled cubbies. What struck me about these kids was that they’d say: ‘Ah, that isn’t gonna happen’. ‘No it really is’. ‘But we’re not gonna fit in them’. ‘Oh yes we can, we’re gonna fit six kids in it’. So what struck me was this amazing disbelief. In knowing the town’s history, it was most important that these cubbies somehow stuck together, that they did them. They can’t use any power tools. A rickety handsaw was all we had.

And did they come up with their own ideas about the cubbies?

Yes, absolutely. They started with drawings, and these drawings became the houses. I had just got this job at the -University of Ballarat Arts Academy and then I thought: let’s actually link the University and the Eco-Living Festival. Then I thought about how about we get Utako, Ash and Bindi to respond. Because Ballarat had a quarantined set of funds for artist residencies, wouldn’t it be great to get these guys in to look at different ways of sustainability? I thought that for Bindi it would be related to an Indigenous sense of sustainability. Utako being the globetrotter that she is, how do you maintain that cross-cultural sustainability? And for Ash, it’s a natural thing, working with reclaimed rubbish. So it was that underlying thing of truly hitting a region with sustainability. I’m sure something rich has happened and continues because of these works.

I’m interested in why you selected these individual artists.

I knew their work very well and they were the obvious choice really, in the sense that I did stick pretty closely to the concept, which of course could be broken open again. I thought each of them had enough flexibility within their practice to really be able to take on an idea, to take on a site and produce something very provocative.

So you really spanned the generations with this project by working with primary school children, emerging artists and then more established artists like you and Lyndal?

Yes. I think that environmental sustainability is not only an ecological question — it actually hinges within a cultural attitude. So, it is important to work with kids right up through the generations. I guess my own role as a performance artist in the video and photography area, I’m not necessarily so able to translate the science, but I certainly can work with others in waking up an imagination. And I think that’s what happened with these kids.

Which goes back to this generational art issue — what you were discussing earlier about a culture in pain. It comes up through the next generation. Are they the sort of ideas that you briefed Bindi, Utako and Ash on?

The brief was very loose — they all come from different points of view, if you can think about how you can work it within the theme of sustainability — I mean, sustainability as a word has 36 different meanings. So I chose them for the show Sustainable Fusion Reactions. Pick something that really fits, but of course we are in Ballarat and Avoca. The idea really is to have one part of your consciousness in the place where it will be shown. That was a unifying thing really.

Bindi, you collected rubbish from your traditional Indigenous ancestral land. How did you first associate with the land when you started thinking about the project?

At the time, I was thinking a lot about language. And I had just come back from the Tiwi Islands where I’d spent a number of weeks. I’d become really aware of the loss of culture, and the biggest loss of culture, for me at least, was language. If you take away a person’s language, you’re completely dispossessing them from their culture and their land. It was on my mind. It distressed me a bit, coming from a place where they were able to speak their language, and knowing that my ancestors were not lost or dead but removed, on purpose too.

When I came back and started this residency, I saw that there were strong links between language and sustainability, or culture and sustainability, and how the language had been thrown away like it was rubbish. I thought about how I could revive this language, in a way that is related to sustainability, especially being on my own ancestral land. Driving from Melbourne to Ballarat and seeing all the rubbish thrown from cars on the road — thinking about language and how it is thrown away like rubbish out their car windows — I had this idea to make the language out of this rubbish, and turn something that has been thrown away and deemed valueless into something valuable.

What was interesting about building language out of rubbish is that it almost ended up looking like wreaths of flowers and letters that people use in funerals. And I didn’t work towards that — it was just one outcome. It looked like a funeral or memorial, which also sat quite well with Ash’s work.

What was important about the words that you selected?

The words that I selected were Wathaurong words and words that were significant to me, such as the words for ‘father’ and ‘daughter’. It’s protocol in the community to discuss your ideas with elders, so I always do that with my dad and with different people in the community. I made the word for ‘father’ and I took his portrait.

Is that reflective of the type of collaborative work that you do? It no longer becomes the single artist as author, but something that is owned by many people, a community?

Yes. I’ve been talking with another artist who involves her family with every piece of art she makes. It does make it richer, and it makes you closer. They’re both important things for me and my family and my community.

Those types of storage and dispersion of knowledge are so rich in Aboriginal Indigenous culture and it’s also strong in Asia. Maybe it’s a little bit lost in Western traditions. It has such a rich way to represent the culture.

Utako, can you tell us about some of the other work you’ve done in Japan before coming to Australia?

I describe my work as site-specific installation, because I ask a question of the place, so the site becomes very important. I consider how you engage with the space or the context — it could be architectural or social or conceptual — and how you relate through your artwork and also through your being, as an artist or person, to the place.

My practice starts with drawing and sketching the environment, and combining Japanese with English in audio surrounding sounds, into abstract drawing, or eventually using photography or video to create a similar sensuous engagement with the surrounding environment — to create some sort of imagery to stimulate people’s memory of a particular place or feeling. But eventually my idea was to focus on us and nature. Not necessarily spectacular or lurid, but maybe urban — street trees, sun viewed through the window, or light on a basketball court in Carlton Gardens.

Eventually I really discovered my almost natural way of engaging with surrounding environments through animistic or Shinto way — that’s very much a Japanese traditional way of seeing the spirit in nature or in life. Life is not individually separated but interconnected across different materials and substances.

I don’t know why, but I thought it fitted with the ideas of cross-cultural sustainability. And also Avoca and Avoca House relate to migration and actual living. And that was also a really good way for me to reflect my eight years of being in Australia, and also a great opportunity to engage with really exciting local artists — Ash and Bindi — who genuinely care about the culture and landscape.

DH — Did you find that your perspective changed coming from an urban environment to a remote one like Avoca?

I felt so alien there. And really got to understand how dry Victoria is. It is actually so different from the wet, humid, rich rain environment I know in Japan. But this time, when I was there, it wasn’t too bad — we had a bit of rain. But still there were restrictions with the use of water in Lyndal’s house. I learned how to live with minimum water. So, I knew that Australia is dry and I knew there is a rich -Indigenous culture, but being in Melbourne I didn’t really get to experience that. So being in Avoca, it didn’t change my perspective but gave me a really good experience.

I started being really attracted to puddles and dams and reflections of the sky, and what the sky looks like, how much it stands out if there’s water because it’s so dry. That’s how I started to relate to issues of drought in the community, and also in sustainability in environment of climate change. I made an installation piece which intended to indicate the idea of actual water and climate change by using acrylic mirror and that reflective quality of putting it on the ground. So I was trying to talk about water, trying to mimic the reflection of the puddle, but photograph the sky of Avoca and print on clear film, which I could put on glass. So you’re in the indoor environment, but you’re actually seeing outside.

Ash, can you tell us more about the flag work you made for the exhibition and how you first approached it?

Jill invited me knowing part of my practice that involved large intersections with commercial and industrial waste, and actions and projects around materials like that. That’s something that started heavily two and a half to three years ago, leading into 2020, with a couple of waste-audit projects. It was site-specific, and that is also where there is a connection between Utako’s and my practice. It has been important to me to make works that are site-specific, and relational to audiences who are going to see my works. In that regard, I had done what I needed to be doing — which was intersections between commercial wastes. There was a simple parallel that those pieces of timber were once trees. And so there was an idea that I might use those and invert them vertically, as opposed to horizontally, very early on.

Ballarat is such an interesting city visually, with its flagpoles. I instantly thought about the more historical aspects of the area and saw that there were some interesting parallels between a need for an uprising against authority — be it community-based, more than anarchic in the future, but to create a freedom for the environment — a simple parallel of Eureka. So that was the initial concept that I started running past Jill and, as we started getting going on the idea, the opportunity came up to speak to one of the three descendants of the original Eureka flag makers.

At the installation we were looking at the thirty railway sleepers, piled up in a flat rectangular shape, and then the flag was to be laid ceremoniously across the top, then there were videos of all the different sites around Ballarat with the flags flying that were part of the installation, and then another video of the flag at Avoca House. And Ash said: ‘the death of the industrial revolution, awakening of the green revolution’.

The railway sleepers were a plinth for the flag, but also a coffin for the flag to lie on. The stacks represented the history of the area, whereas the flag was newly made and didn’t have that history. The change of the colour represented a new take, if anything, an opportunity for a new history to write itself. The Eureco flag for me, first and foremost, was a personal tribute to my mother Pam Keating, who tragically died in a car accident at the start of 2009. Changing the Eureka flag’s colour to green, was part of my healing process and a way to show respect to mum regarding some of our last conversations we had together regarding the world’s environmental crisis and her passion and commitment she gave to the cause.

It has a connection with the funereal and memorial qualities of Bindi’s work — associations of death and renewal. After these experiences and these works, are there things that any of you took out of it that you would incorporate into your practice?

For me, it was my first attempt at a large-scale installation. I’d done photo-graphy and a video piece, but I’d never really attempted installation before. It was something I’d wanted to do, and that I will continue to do. I’m studying at Ballarat Uni too, and I was studying drawing and digital. I switched afterwards to media to accommodate this shift in my practice and also in language. There’s a really selfish part to wanting to explore language. There’s a righteous part of wanting to revive it, but also a selfish part in wanting to learn it. So it served two purposes for me — wanting to learn the language through the revival and its practical impact on my work, for years to come I’m sure. But it was the very first time that I explored it.

From my perspective, before we knew where anyone was working, I asked if Lyndal would fly my flag out the front of her house. So I went out there and Lyndal had her Sunday best on and was running around like crazy, getting her house ready for the festival. She helped me and we put it up. It was great for it to work in concept and in my mind. There were three medium sizes — one in the Art Gallery of Ballarat window, one under the flag on Trades Hall. So I found all these areas of possibility and narrowed it down. Part of my project was just trying to connect and get people interested on board. People from Trades Hall were very responsive, whereas others weren’t. Not necessarily because they had a stance on the issue, but more so because they were afraid other people would.

There are also the associations between the Eureka flag and current trends in using the flag to represent neo-nationalism in Australia. And that’s a corruption of sorts.

More so the Southern Cross.

Yes. But it could be considered a corruption — the use of symbols has a tradition of being appropriated, inverted and corrupted. Did you think about that in your appropriation of the Eureka Stockade flag?

Yes, but I don’t think that the Eureka Flag necessarily crosses over so much as does the Southern Cross or the Australian flag. I think it’s quite specific and loaded with a lot of personal strength and history.

I see some sort of cultural symbolic connection between neo-nationalism, the White Australia Policy, the dominance of European culture and the attempted genocide of -Indigenous culture.

There’s no doubt about that. I’ve never worked with historical symbols such as a flag. I try to work with different materials and mediums, site-specifically to bring new questions out. So if it raises questions about that, then good.

Would you say it’s the recycling of a symbol, in the same way that you recycle and intervene with other waste?

I would say it’s more about connecting with something that people are both proud of, but also holding onto. I’m not necessarily talking about the Eureka Stockade, but the difficulties we face in terms of dealing with the environmental crisis. It’s more about showing respect to history, but repositioning it and creating a new path and awareness of the history.

It’s interesting though, because there is a difference between making a statement and a proposition. And I think that the whole issue of flags in Australia at the moment is becoming quite weird. So I like the idea of the danger. If it were simply a safe transition from blue to green, it may also link to the fascistic element of the green movement.

Yes, this has certainly been raised.

It’s something I became more aware of leading into it. The redesign, albeit in a limited context, it’s still in the public domain. There wasn’t any outrage here or in Ballarat or online via the blog. So it’s out there, if anyone wanted to stir it up, I thought it would have already happened.

Previous to going to Ballarat, I did a project in Penrith, New South Wales. I was swamped everyday with utes and houses — I’ve never seen the Australian flag used so intensely. It’s what I knew of from a distance. That’s really intense out there. So I was quite aware of the symbol in that regard.

I do think that symbols always have their underbellies that pop up through the seams. So, in the end, it’s this massive dialogue between pure racism, which is the underbelly of this country in a way.

If you position my work in terms of that, it connects with both Bindi and Utako’s heritage and the way in which they were making art in that area.

As kids, it felt like the Eureka Stockade was the first uprising against authority — besides the battles that Indigenous cultures waged against colonial order, which have been written out of the history books — it was a real changing moment in the character of Australian culture.

To put it into context, like now, the changing of the colour is just a catalyst for the same change — a change of mindset about the urban sprawl, as opposed to a much needed community focus on density and a new way of living and operating.

The Avoca Project and also Sustainable Fusion Reactions both happened in an area and community where people are living, not because they’re art lovers — we are making an event with art as part of its means. The event was not for art, but rather for producing an opportunity for dialogue and discussion. For each of the individual artists to explore bigger communities and discussion, on different levels, so Ash’s work ties in very well to some attitudes. From my point of view, that ties really well in relation to the direction we’re heading towards.

It’s like a logo, not just some symbol — I think sometimes people can be too sensitive about using some sort of symbol in artwork. It stops artwork and art events from appealing to other potential audiences. It’s not about being controversial — it’s about trying to be more accessible and attractive.

The danger of symbolism, which is happening now with the Southern Cross symbol — tattooed on bodies, as bumper stickers on cars — people wear that because they see it as a correlation between something that is distinctly theirs, not European, only Australian. Then that begets the question: ‘what is Australian?’ We still haven’t really dealt with that, like we haven’t dealt with Indigenous culture and immigration.

It’s got all those connotations about dispossessing Aboriginal people.

But I think that’s part of the interesting sweep across each of the projects. It’s as if everyone’s historic inheritance has been put on the table in some form or another. It is part of the dialogue.