Jake Wotherspoon’s Opening Performance (2010) for Re/Gendered at Platform featured a creature, too hairy to be human but not hairy enough to be ape, reclining in a cabinet.1 With a derisive stare articulating the boredom and misery of the caged curiosity, its gaze was directed at the crowd and the cabinet beside it housing two photographic portraits of longhaired, bearded subjects. Given the circumstances, the creature could well have been saying ‘All this fuss over a little hair?’ Had that been its script, the words would have played out well as irony — absent since the opening, all that we had left to remember the sad figure by was a video documenting its debut into civilised society and sparse mounds of shed hair piled up on the cabinet floor. As the embodiment of hair itself, Wotherspoon’s creature played to Judith Butler’s famous account of gender performativity by scrambling a primary gender signifier, thus risking its exclusion from the species ‘human’. Becoming ‘natured’, and thus beyond gender, the haired thing’s situation demonstrated the cultural inscriptions responsible for producing an array of seemingly fixed, biological distinctions.2

As a phenomenon, hair articulates the complicated and sometimes contradictory efforts to draw a line between the natural and artificial. Hair is bodily but it is also dead, making its constant styling and modification easier and less painful than other bodily alterations. This susceptibility to change operates in an inverse proportion to the strong cultural association that fixes hair to biological destiny. This is perhaps unsurprising. Whilst hair places humans in the category ‘mammal’, class-wise we are seen as virtually hairless — one of our defining characteristics is noticeable through its absence. This fragility of classification extends to the social where sexual identity is manifest in delicate balances between hairiness and hairlessness. An ideal woman, for example, is hairless except for her head where long, luscious locks compensate for the bodily deficiency that could threaten her claim to being a mammal. But hair on a woman’s upper lip, legs, or toes is surplus, leaving her prone to a hirsute masculinity. A man with too little hair similarly runs the risk of being thought effeminate or old. Too much of it, though, reclassifies him as a ‘beast’.

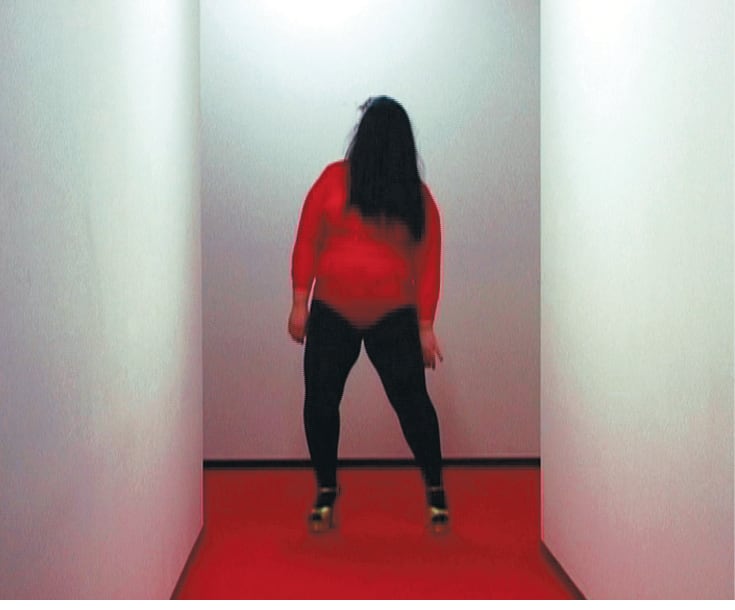

As well as marking gender, hair can be used to conceal gender, thereby confusing the structure of viewership that relies on the power of the voyeur. In Drag Acts (2010), Fran Barrett, Kate Blackmore and Anastasia Zaravinos draw attention to the connections between gender and sex appeal. Depicting the wilderness of human sexuality that exists at the interstices of urbanity and gender, the video piece features a lone figure dancing provocatively under the harsh lighting of a motel or hotel corridor. With long black hair covering the face, a scarlet knitted top and matching bottoms, black stockinged legs and high-heeled shoes, the figure recalls the aesthetics and the gestures of the strip club or private dancer. While we presume the figure to be female, the suspicion is never confirmed. In this work, hair appears initially as a veil, manipulated to heighten sexual mystery, however, as it becomes obvious that the face of the performer will never be revealed, the hair becomes more like a curtain behind which the performer ultimately hides his or her identity. As well as raising the possibility that the hair conceals monstrosity or deformity, the performer disrupts the association between hair, bodies and sex by calling into question the tightly monitored relationship between sexual appeal and gender.

The manipulation of hair is just one of the devices called upon to destabilise the conventionally powerful looking position of the viewer. Without this gender certainty, the viewer cannot claim to ‘possess the object of the gaze’.3 We might think of this as resulting from a deliberate artlessness. It is Freud who, in discussing the relationship of art to truth, observed that art provides us with a form of mediation that enables us to enjoy personal daydreams without shame.4 Drag Acts exploits the tension between the carefully constructed artwork and the seemingly shameless excess that articulates, rather than aestheticises, the reality. The dancer’s black hair is too messy, indicating the aggression of the head-banger rather than the light playfulness of the tease. The tight fit and drape of the figure’s torso cladding accentuates its barrel shape and the luscious mounds of flesh comprising it. Rather than deferring to the modesty of the dancer afflicted by bodily ‘imperfections’ — a shyness in itself which reinforces the power of the ability to look — the dancer in Drag Acts proudly declares his/her body an object of self-worship, awkwardly caressing it as a form of offering to anyone who will watch. High-heeled shoes contribute to the unsteadiness of the routine that looks increasingly intoxicated. The performer bends to the floor in an unflattering squat and then worms his/her way back into an upright position. Usually finger-licking and a hint of genital exposure are a cause for titillation, but here these gestures cross the bounds of expected eroticism. Ultimately, it seems as though this dancer is too drunk to take our gratification into account. Even if not intentional, the piece works as a reference to Beth Ditto of neo-new wave outfit The Gossip. Ditto is known for her overtly sexual performances as much as she is for her voice. As an attractive ‘fat’ woman, Ditto herself challenges stereotypes about what constitutes ‘sexiness’ by creating a stage persona that boasts a genuine sex appeal — one that is noticeably absent from the polite eroticism offered by pop stars. Drag Acts presents us with Ditto’s less appealing twin and, in doing so, subverts Ditto’s own subversion by declaring out loud the voyeur’s shame: without the proscribed modes of eroticism that lean towards the tidy conventions of gendered desirability, desire becomes unknowable, unwatchable. The voyeur loses control and the apparently superficial instances of hair and style are revealed as indispensable to a strictly demarcated system of meaning that defines how sex operationalises desire.

It would be remiss of me to put forward a discussion about the relationship between gender and hair without mentioning last September’s Blue Sunshine exhibition at TCB art inc.5 As both counterpart and counterpoint to Re/Gendered, Blue Sunshine emerged from the observation that the initial participants — Charles O’Loughlin, Jackson Slattery and Matthew Shannon — were all bald men and that they were often confused for one another. Here, the lack of cranial hair suggests an interchangeability that denies the import of other common identifying characteristics like height, face shape or sartorial style. The exhibition was open to any bald artist who wished to make a piece about being bald and included work by Lane Cormick, Warren Taylor, Damiano Bertoli and Daniel Moynihan. Unlike Re/Gendered, these works about baldness and a certain doppelgänger effect — another condition noted by Freud — were premised on baldness as a common, masculine condition that requires some form of recognition. The association between hair and gender is seemingly fixed. But of course, this curatorial condition acts as a perfect counterpart to the propositions at Re/Gendered’s heart. Because hair — or a lack thereof — reinforces the fact that hair matters to the extent that, beyond gender, it has the potential to erase individual identities. The tone of Blue Sunshine’s proposal and press release all suggested that, conceptually, the show was not intended to be humourless. Tongue-in-cheek observations can certainly be made about Damiano Bertoli’s predilection for incorporating smooth, hard, highly polished surfaces into his practice, a tendency exploited to great effect in his work for this show. That did not, however, prevent these works from offering up some interesting questions about the delicate social definitions that hairful- and hairless-ness maintain. Why, for example, would we confuse two dissimilar bald men of a certain age when the glabrous are almost as prevalent as the heavily thatched?

It is implicit in Blue Sunshine and Re/Gendered that hair provides an aperture through which to witness the politics of sexual identity. Hair’s capacity for manipulation seems to guarantee its status as a rigidly monitored social code that maintains and troubles gender distinctions. With long, curling tresses spilling over his smooth shoulders and accompanied by the trademark ‘Carrie’ necklace, Liam Benson’s ode to Carrie Bradshaw, Thankyou Carrie (2009), works as a perfect summary and address to these concerns. By not deferring to the tropes of drag, Benson prompts discomfort — we are presented with a man who has adapted Carrie into his shared facial characteristics, acknowledging both simultaneously the machismo in Carrie’s raunch culture and the girly character worship in Liam’s. This is how Thankyou Carrie gives concrete form to a profound social fear — without the seemingly dramatic force required to turn a man into a queen, or the loud humour enabling women to adopt the personae of teenage boys, we are left with a man not needing much at all to achieve a convincing representation of femininity.