There are some activities in life that have a natural way of bringing people together. Real things: talking, cooking, craft. With each of these communal rituals, the central act of coming together is often more important than the products produced.

Long before the concept of community art centres or Stitch ’n’ Bitch cafes,1 women were congregating in huts, kitchens, sewing rooms and lounge rooms. Together they were chopping, stirring, sipping, stitching, painting, plucking, embroidering, enamelling, eating and, of course, talking up a storm, at regular meetings the world over.

It is interesting to look back at the sentiments that arose around the 1970s Women’s Art Movement (WAM) meetings and recognise that it was as much formed by a desire to regularly get together, talk and be involved in something at a grass roots level as it was to establish and defend the rights and future of women in the arts in Australia. Political action grew from community gathering. Janine Burke recalls: ‘perhaps the most liberating aspect of the women’s movement in its early years [was] a ready-made, do-it-yourself quality. If you had read the books and had a few sympathetic women friends to discuss them with, you had the women’s movement, right there in your kitchen’.2 It was this time in Australia that women achieved a political and creative synergy which still continues today.

One artist to come into view during this period was the radical and prolific -Vivienne Binns. After making a vibrant -debut in 1967 with her psychedelic paintings and pulsating sculptures of ferocious-looking vaginas and yonic visions, she outraged the Sydney art world. According to Merryn Gates: ‘The rigid avant garde in the 1960s couldn’t embrace her style or her subject matter. There was just no critical pigeonhole for abstract work which asserted female sexuality and addressed repression and censorship’.3 Binns, full of fire, went on to make a life-changing decision. Unheard of for someone at the beginning of their promising painting career, she decided to take to the open road to work with ‘real people’.

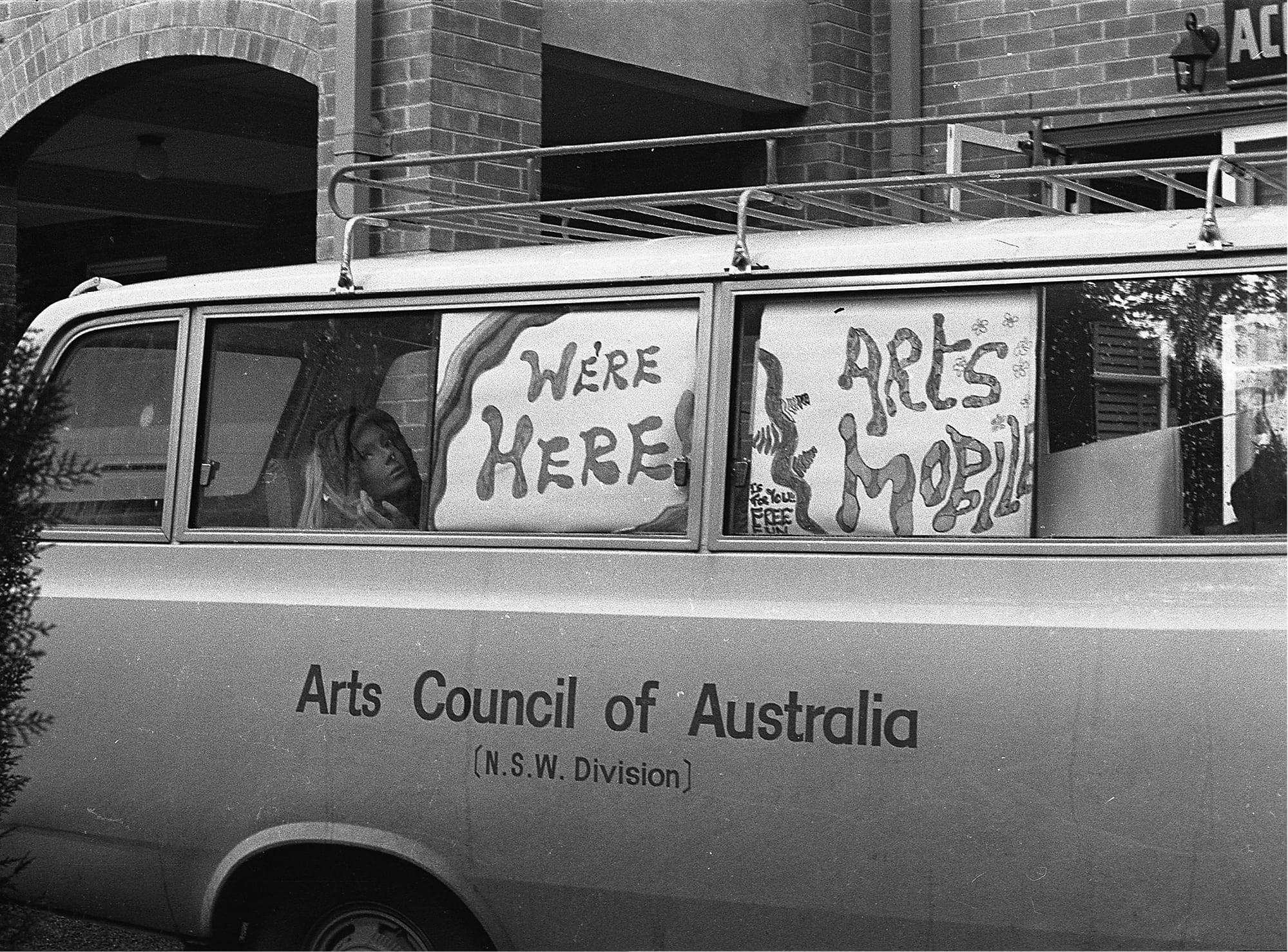

Starting with the Artsmobile project in 1972, she drove a converted bus around to regional communities initiating craft, performance and participatory activities. Described as ‘the offspring of a marriage between Fluxus and a local town council bookmobile’4 this work allowed Binns to connect with a reality beyond the restrictions of the art world — a reality that satisfied the basic human need for compassionate retelling of life’s hardships through creative practice.

Binns went on to initiate a project called Mother’s memories, other’s memories in 1977 where participants — often wives and mothers — were encouraged to express skills and memories passed down from their mothers, manifesting in pieces such as Scenes from the highway of life, where sentiments from a group of many different individuals both artists and non-artists were hand-made into steel enameled postcards, which were then displayed on the type of rack you might find in a country town souvenir shop. Binns was interested in genuine participation — art for anyone to get involved with. Her work not only focused on the crafts and objects created by ordinary women, but more importantly drew a picture of these women and their lives that were often otherwise invisible.

Binns was a trail blazer in making the personal political, recalling: ‘the years of work as an artist in community were always part of my work and not part of “dropping out” as it seemed to some, who were locked in the notion of an artist working in a single medium, a recognisable style and producing a regular stream of objects’.5

In 2010, Melbourne collective the Hotham Street Ladies is not so much following in Binns’ footsteps, but rather travelling that same broad highway, carrying the flag for strong-willed, independent women in a manner that is perhaps more celebratory than revolutionary.6 Growing out of a friendship formed whilst living together in a rambling share house in Hotham Street, Collingwood — hence the name — the ladies began by collating a humble version of a CWA-style (Country Women’s Association) cookbook. They are now onto their second edition, with their combined recipes and content from friends and family including a section written by their mums. Their raffish, craft-centric practice has grown from the books into numerous collaborative projects ranging from guerrilla-style, site-specific icing of giant cock-and-balls onto the roads of Newcastle, to entering an elaborate, half-eaten pizza-in-box cake — complete with grease stains, TV remote control and butt-filled ashtray — in last year’s Art, Craft & Cookery Competition at the Royal Melbourne Show.

In comparison, the practice of the HSL is like a cheeky Generation X cousin to that of Binns’ — confident despite its apparent lack of expert craft or cooking know-how, with their determined success relying almost single-handedly on their shared strength and commitment to each other and their idea of community. Their inverted domestic actions of icing graffiti onto the road also challenge the more masculine business of tagging and ‘vandalising’ the public realm with a sugary and ephemeral statement, albeit laced with irony.

The following excerpt from their most recent cook-book, HSL — Hotham Street Ladies’ Tastes from a Shared Kitchen, helps to reduce and explain some of their core motivations:

Making Stock

This is not so much a recipe as an acclamation. It’s not that I’m any expert at making stock; I’m just an enormous advocate for this highly satisfying activity … So, I do hate throwing out food and I do hate using little salty msg cubes made by a multi-national. I also get terrible guilt when I’m not doing anything. Making stock addresses all these anxieties.

— Lyndal Walker

All the battles that Viv and her WAM contemporaries fought in the 1970s, and later on the rocky road to establishing community-based art, have helped pave the way for Australian women like the HSL and to open the door for many to come. Although not without potholes, the road is lined and surfaced these days. It’s commonplace for creative women like the HSL to not only make and sell art — although, only Lyndal really calls herself an ‘artist’ — but to be paid for creative jobs in education and own and run their own creative businesses, such as jewellers, homeware designers, visual merchandisers, landscape architects, which was rare forty years ago. For HSL, it’s very much a case of baking your cake and eating it too — perhaps all they need to do now is form a band, get a bus and take it on the road.