The monument as a public art form has had a significant impact on art history and the way in which civic space and the geography of cities have been experienced. Yet the monument has a more complicated function than its official status as memorial.

Its heroic subject matter and dominant presence in public space allow the monument to assert itself as a symbol of the ever-watchful eye of systems of power. In this sense, we can begin to consider the monument as a manifestation of the panopticon — an unrealised plan for the ideal model of an enlightenment prison designed by English philosopher Jeremy Bentham in 1785, and later developed into the social theory of surveillance by French writer Michel Foucault. Ultimately, however, the perceived inertia of the panopticon as a built structure is inconsequential. This is because the power of the panopticon lies not so much in the constant surveillance it portends, but rather in its pacification of inmates (citizens) by encouraging states of dehumanising paranoia that provoke submission, such as those experienced at Abu Ghraib. The monument does not actively restrict movement but acts instead to instil a permanent sense of the need for decorum in citizens’ minds. In turn, this has the power to alter citizen behaviour by subtly enforcing greater conformity through an appeal to individual civic pride and passive acquiescence.

By the twentieth century, the building of monuments had come to be seen as a philosophical farce within modernism’s surge to abandon the past in favour of the future. Nonetheless, during this time the production of monuments was pursued as zealously as ever. It could even be said that the past was fetishised to a degree; a part of what Andreas Huyssen has termed the ‘memory boom’.1 Post-WWII monuments were produced with an especial awareness that the hope for longevity was simultaneously an acceptance of the transience of history and its mythologies. Today, this uncertainty is frequently built into the very structure of new monuments. For example, Sydney houses a unique monument to -ruins and the decay of monumental structures in the work Memory is Creation Without End (2000) by Kimio Tsuchiya. This piece is a public sculpture located on the edge of the Botanic Gardens and is composed of the remnants of demolished colonial buildings.

Since the 1960s, public spaces have become increasingly inundated with public sculptures. British writer Judith Collins has observed that sculptures in public spaces have replaced the monument with monumentality — retaining only the scale and prominence of monuments whilst dispensing with their ideological function.2 These sculptures often appear as though they had drunk the growing potion from Alice in Wonderland. While formally considered, these works are mostly insensitive to their surroundings and mute about the contextual politics of their existence in public space; they are examples of what has come to be known as ‘plonk art’. Of course, there are instances of public sculptures that are extremely in tune with their surroundings, such as the iconic and famously removed Tilted Arc (1981) by Richard Serra, but these examples are few and far between.

From the early 1990s, new types of public art projects became commonplace, with a focus on community involvement in works that were more deterritorialised and process-based. In the end, both these types of public art — the non-specific monument and its dematerialised cousin — implicitly communicate something of the values held by the various commissioning institutions responsible for their funding. In contrast, public sculpture projects commissioned by corporate companies are usually concerned with the simple decoration and enhancement of a space. In general, such sculptures are commissioned to comply with a capital friendly aestheticisation of public places, their only conceptual premise being a work’s ‘wow’ factor. Curiously, the passivity of these projects is often critiqued through the alternative commissioning of public art interventions by public art institutions. These projects valorise an alternative type of monument dedicated to broadly democratic values like communication and non-hierarchical dialogue.

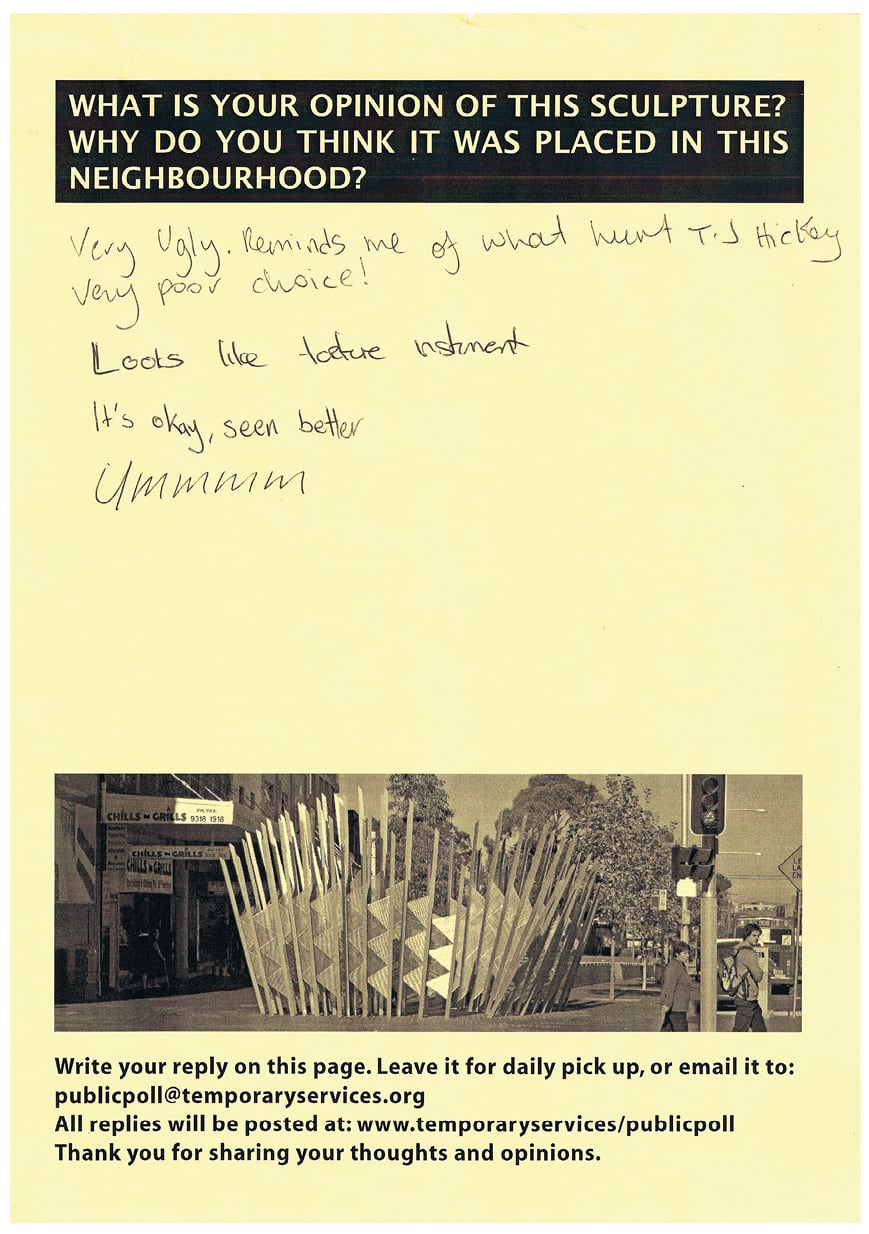

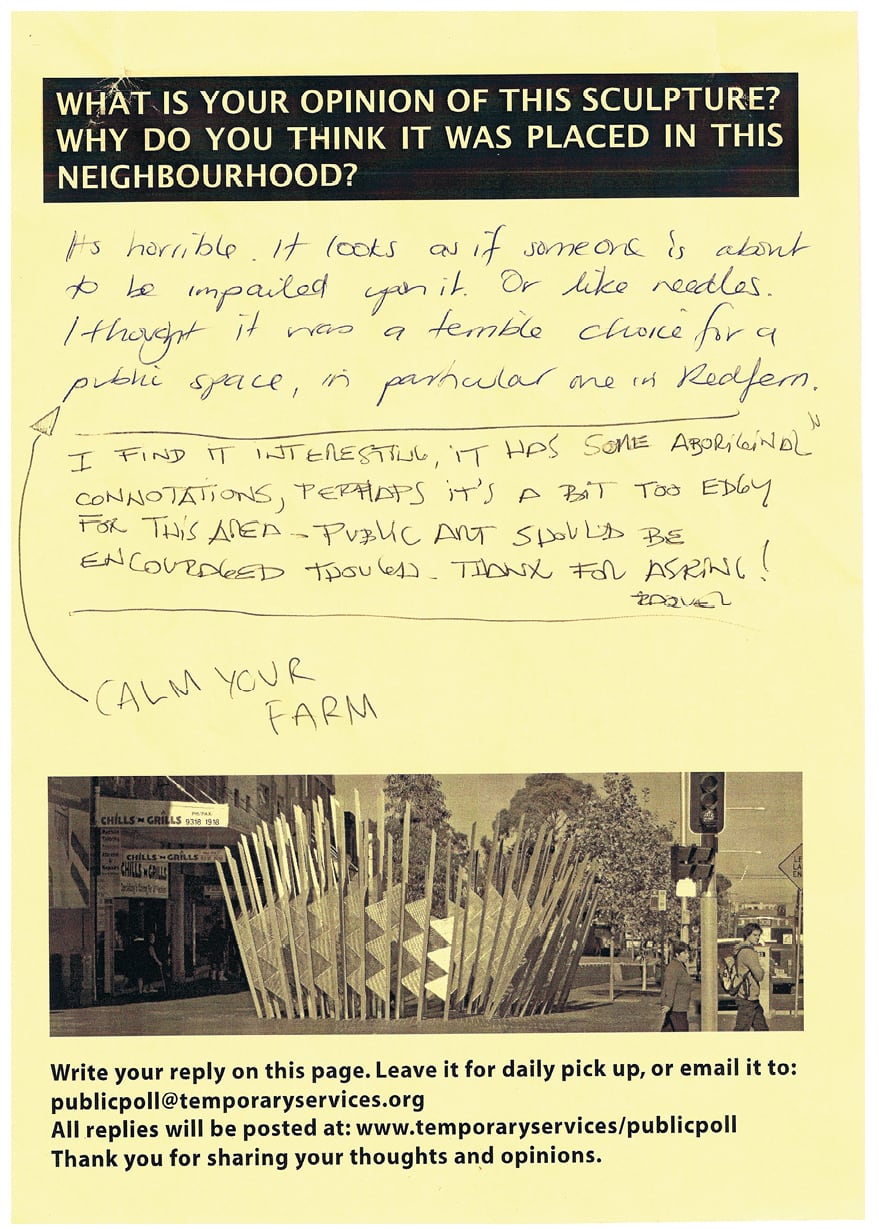

A rather direct example of the interaction between the realms of corporate and performative public art was recently invoked in a 2009 project in Sydney’s inner city area of Redfern produced by the US-based art collective Temporary Services, as a part of the There Goes the Neighbourhood exhibition. This exhibition aimed to encourage local discussion about the effects of gentrification on the area. Temporary Services conducted the Public Sculpture Opinion Poll in response to Bower (2007–08), an aggressive-looking sculpture by Susan Milne and Greg Stonehouse. As a part of Temporary Services’ project, a clipboard was placed on a telegraph pole in view of the public sculpture that invited passersby to leave comments about how they felt about its insertion into their neighbourhood space. This served to further bring attention to the myriad socio-political entanglements surrounding the particular placement and context of this public sculpture and the performative response of Temporary Services’ poll.

Monumentalising democratic dialogue and access, however, in no sense evidences sinister motivations, unlike those underlying the many monuments produced during the nineteenth century that eulogised the colonial nation state. Nevertheless, the type of communication on offer with regard to the performative monument is more choreographed. In essence, it allows only for a performance of communication, rather than a dialogue that is natural and open. The work becomes a signifier or a prop for mere processes of interaction and, as a result, a monument to unfulfilled democratic hopes. The need to perform communication clearly signals a desire to feel a sense of connectedness — a feeling that, despite all the technological advancements employed to connect people, seems sadly lacking in the contemporary world. If people actually felt that they were being heard by the state, then there would be no need to produce monuments commemorating and extolling ideas of communication.

With these notions in mind, Sydney based artist Astra Howard recently produced a series titled Action Research / Performance Project (2007). Howard produced and performed inside a monolithic, transparent booth where she communicated with members of the public by writing on its walls — allowing viewers to reciprocate her gesture and create dialogues by writing in response on the outside of the structure. Considering the documentation of this work, it seems as though Howard was lending her body to animate an obelisk and, in doing so, humanise the monument. This possibility seeks to equalise the imbalance of power between the monument and the citizen. By shifting the monument’s traditional signification of historical continuity and permanence, to a temporality favouring contemporary ideas around immediacy and ‘presentness’, the artist allowed the inscriptions accrued on her monument to be in a constant state of renewal.

This type of monumentalisation of social interventions interferes with the incessant mobility of contemporary life and places a question mark before the habitual stream of everyday consciousness. These interventions provide a moment of rupture in otherwise overly structured, often repressive urban environments. In this way, they could perhaps be better understood using the notion of ‘the accident’ as imagined by the French urban theorist, Paul Virilio. In this way, these performative sculptures are a welcome derailment that can cause conflicting feelings of discomfort because they require a readjustment within an otherwise familiar situation. At the same time though, they also concretise the pleasures of novelty and intrigue.

A durational intervention by Welsh artist Phil Babot was performed in this way as part of the Trace Collective project for Artspace, Sydney in 2009. Performing a basic action on an everyday site, the artist brought the repetition of daily existence into question. Babot used sandpaper to scrub away layers of grime on a corner in Sydney’s Darlinghurst. Through his scrubbing action, Babot produced a symbol of a cross that pointed towards his hometown in Wales. In physically undoing historical residue through the process of rubbing away, he produced an anti-monument to the colonial and territorialising presence of the English in both Wales and New South Wales.

Many other artists create public interventions that exist as temporal fragments in space. Not necessarily commissioned or even meticulously documented — other than as rumour or ephemera — these actions can be seen as monuments to notions of instability and transience which have become ciphers for our time. One such work was a description of a 2009 performance by Sydney artist Victoria Lawson titled Momento Mori: Remember that we are all going to die (the artwork makes me immortal / the photograph kills me). This work was enacted in the town of Evora, Portugal, which is UNESCO listed and thus already a monument to itself. In considering the nature of the historic preservation of sites and their role in ‘memory tourism’, the artist inscribed two marble tablets with the inscriptions ‘the artwork makes me immortal’ and ‘the photograph kills me’. These were used to mark two points: the first in the historic centre of the town, and the other outside the city limits a significant distance away. The artist then walked to the point of exhaustion between these two points whilst meditating on texts that were influential in the shaping of this action.

The existence of works such as these — while they have the ability to subtly displace daily reality — depends primarily on the production of a proposition or symbolic gesture. They do not always rely on interaction from the audience but they exist as subtle reminders of the transience and unsettled nature of the contemporary condition. The contemporary focus on being present is now at odds with the notions of continuity and stability suggested by the durability, scale and steadfastness of the common monument. Monuments of this sort can no longer be built without considering their incongruity in relation to the speed and plurality of contemporary modes of existence. Indeed both extreme speed and fragmentation preclude the reflection necessary to envisage a convincing shared mythology.

Despite this uncertain condition, the urge to monumentalise mythologies and experiences appears to be a vital need in civic experience and thus a necessary function of art in the public arena. In the absence of the stability needed to produce common monuments, the prior social function has been usurped by repeated performances of the very notion of both the monument and of monumentality itself.