Street art constitutes a diverse set of acts, gestures and mark-making insinuated and acted out within the physical space of our daily lives.1 The unsolicited creativity evidenced within the public sphere is a means of expression not only restricted to rebellious spasms, but more expansively to an articulation that seeks the pleasure of taking an idea and making it material in the public domain. It is an opportunity that is seized before the shadow of a new thought passes the mind — a physical act released before circumstance dissolves into a new set of possibilities.

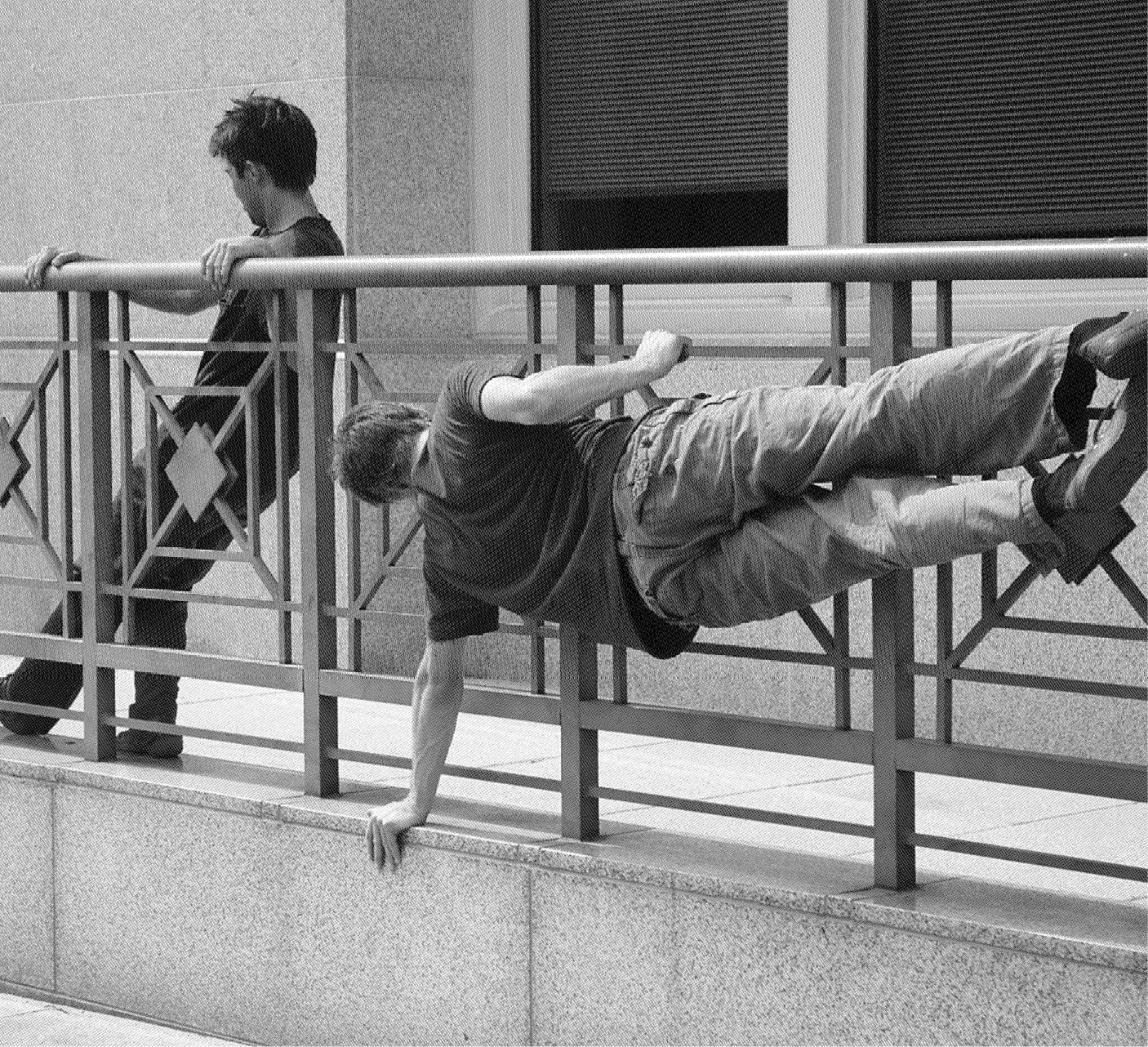

Creativity that operates on whim is an act of ‘making something for oneself’ out of the ‘material’ of the moment — a mark, a statement, a protest, a poetic, out of and on to whatever one finds at hand.2 As a practice, street art adheres to the spirit of experimentation in that there are absolutely no rules apart from the physical laws of nature. It releases one from expectations — including those of your own making, provided you can abandon them — to engage in an activity where ability, justification, explanation and permission are not predetermining factors. In this making without rules, the outcomes are as variable as the forms of practice undertaken. The ‘game’ is enabling a relaxed creativity, one that seeks an enjoyment freed from qualitative judgments, and in turn offers the maker a sense of liberation and play.

By abandoning degrees of control, such as self-censorship, and by limiting the instances where others have a direct say in proceedings, we carve out a space for things to run their course as chance procedures, providing the opportunity for tangents, surprise, and unexpected laughter. A creative practice that entails adherence to too many preconditions — as stipulations or expectations — can interrupt this process, and introduce recurrent roles into the creative process that are more burdensome than beneficial. These roles include managing, delegating, overseeing and, of course, being managed in return. By contrast, street practitioners need merely ask themselves which aspects of practice give them pleasure and act accordingly.

New relationships that afford opportunities also bring new mediating parties. The street artist, who has tasted the pleasures of working unhindered, rejects the most obvious restrictions as compromise. Self-determination is integral to street-based practice; there is the awareness that any autonomy, as fleeting a state as it may be, temporarily creates a sense of pure liberty. This moment is not something that can be retained. You only create respite through practice, and therefore, by maintaining a practice that leans heavily toward self-determination, you allow for the possible repeatability of these moments. Respite can be created and experienced through silencing the constant clamor of mediation.

What of the outward perception and application of street art? It is becoming an almost ubiquitous aesthetic in both the public and private sectors. We now see street art in galleries, retail outlets, blazoned across T-shirts, made into coffee table books and corporate billboards — its seductive and popular aesthetic is used to market a plethora of newly remodeled commodities. We need to remind ourselves that what is lost in the midst of these representations is the social complexity that forms the basis of every public act. If this is forgotten, then the mere trace of the aesthetic of a work can be framed or cropped, and taken as its defining characteristic. It begins to appear, and is treated, as mere ornament — something to catch an eye wearied from other representations. Any work not realised or carried-out in the street cannot be considered ‘street’ art — it is documentation, re-presentation, and resemblance.3 It is an experience without the senses or actual engagement, the moment-to-moment negotiation. What is lost is the enlivening and transformative qualities of actual practice.4 Its reception becomes obscured beneath layers of abstracted meaning and spectacle. The authenticity of the street is essentially obliterated as it dissolves into commercials and theatre. There is not necessarily any intent to distort, or create a fictionalised account on the part of those presenting out of context, this simply is the outcome of an omission, the omission of the actual moment.

The vitality of street art is in its lived moments: the grazed knee, wheat-paste stuck to clothes, the exhilaration of a physical act, of seeing possibilities come to fruition. Public space serves both as inspiration and as support — its walls and bus shelters, its crowds and occasional interested passersby. Street art is a response, an articulation of one’s subjective relation to life — sometimes literal, sometimes obscure, but always as it is experienced in the very spaces where these thoughts are conceived. It is expression made visible within its own context. Artists act publicly, as they desire their experiments to be evidenced, regardless of how subtle their gestures may be. They desire visibility — to provoke, to humor, to bewilder, to be a participant in a diverse culture, which is itself the residue of everyday biological life.

Public space is obviously not a ‘free’ space, where anyone can follow any whim without consequence. As a practitioner, you know neither how you will react nor how you will be reacted to in any given moment. You do not know whether you will evade interruption or encounter something more dangerous. The variability and chance occurrences of the urban environment exist for everyone alike: the casual stroller, the person at work, and the artist who is following the semblance of a thought to produce a public work. Public space is heavily mediated and policed yet this very mediation produces cracks, fissures and opportunities amid the pressure of constant behavioral rehabilitation or subjugation through the phenomenon of gentrification. Yet it remains simultaneously a space of play, of possibility, transit and chance, as people continuously collide with each other and with fluctuating circumstance.

The creative expression formed and viewed in public space as street art could be considered a gift — it is made without expectation of reciprocity, without financial reward, without a specific person as the recipient, and even without a specific intent — how can one know what specific effect will be engendered? In the spirit of gift giving, public art or public gestures are the open source of the physical realm. Cultural expressions circulate without making demands, they circulate freely, never having had rights to relinquish, and they can be engaged with, elaborated, or just as easily ignored. The gift exerts no pressure of exchange or guilt and allows us to determine the route that it will take in our consciousness. However, the gift in one’s mind is potentially an irritation in another’s. We let our gaze brush against the marks of the city as we pass, attentive or distracted, open, biased or indifferent.

Regardless of the response there is a generosity inherent in the circulation of expression made public, a collectivity of ideas based on visibility that cannot be silenced even if occasionally the artist falls into the embrace of authority. The anonymity of the street is an invitation, a challenge, a screen and a laboratory for experiments, a place of generosity, cruelty and harsh reality. Society’s grime, its violence, its poetry and its beauty will be caught in the gestures undertaken in these spaces by its users, particularly its youth, as they discover levels of tolerance, intolerance and degrees of volatility.