There was a sense of urgency to communicate with the objects before our time was up. I had to let them know we are still out here, waiting for them, remembering them; that they weren’t forgotten.

— Julie Gough, Trawlwoolway artist, 2015.2

The title of Soviet writer Sergei Tretyakov’s 1929 essay ‘The Biography of the Object’ returned to us recently as The Biography of Things at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA).3 At the vanguard of ‘factographic’ experimentation in the young Soviet Union, Tretyakov advocated for the end of the bourgeois novel, with its dependence on a protagonist’s psychological interiority. Instead, he suggested a novel could be structured around the lifecycle of mass-produced objects. (Tretyakov’s proposition is a touchstone for the contemporary artist and writer Hito Steyerl, whom I will turn to shortly.) Just as Sergei Eisenstein’s earliest films emphasised collective action over singular heroes, Tretyakov sought a narrative mode capable of tracing social relationships, defined by material interactions, rather than the individualism proffered by the traditional novel.

The ACCA exhibition, along with a number of similar recent exhibitions internationally, suggests that Tretyakov’s prototypically object-oriented thinking has now found its moment, and its place, in museum-based artistic practices.4 According to co-curator (and former ACCA director) Juliana Engberg’s short introductory essay, The Biography of Things brought ‘together several projects that follow material and historical trajectories, gathered, researched, accumulated, documented, catalogued and narrated to reveal the stories sometimes hidden or collided in material culture’.5

The majority of the ten projects in The Biography of Things examined museums, collections and conservation, without the exhibition itself being clearly defined as being about such things.6 One of these museological refractions was Wiradjuri, Ngunnawal and Celtic artist Brook Andrew’s pyramidic, sarcophagus-like glass vitrine, Harvest (2015).7 Beyond this specific work, however, there was little evidence that The Biography of Things was interested in investigating Indigenous conceptions of how stories and meaning might be ‘hidden or collided in material culture’.8

Attitudes to material culture matter. Globally, transversal or object-oriented thinking seeks to challenge dangerous anthropocentric thinking, of which anthropogenic climate change is just one catastrophic effect. In the Australian context, Western-inherited narratives of object mastery and territorial possession are demonstrably part and parcel of the processes of genocide and dispossession that continue to unfold here. Artistic and curatorial practices can continue to feed into unhealthy colonial narratives, or they can become powerful experimental laboratories for the deconstruction and dismantling of these same master discourses. Well beyond the implications of a single exhibition at ACCA, learning from Indigenous conceptions of object relationships would seem imperative in our national context, if curatorial practices are to move beyond imported and transplanted settler-colonial epistemologies regarding material culture.

With this in mind, in what follows I would like to trace a few connections between some prototypical Western forms of ‘object-oriented’ thinking – though addressing the range of current developments in this philosophical field lies outside of my scope here – and an argument put forward by the German artist and writer Hito Steyerl (the subject of my ongoing postgraduate research at Monash University) in her 2006 essay The Language of Things, an argument concerning ‘material translation’.9 Steyerl’s essay redirects one of Walter Benjamin’s writings, ‘On Language as Such and on the Language of Man’ (1916), towards an ethics of documentary-making grounded in the object and – only then, and beyond this – its translation for a human subject. Steyerl makes explicit, however, that while her personal concerns are with documentary her reasoning applies equally to curatorial practices.

Moved by a statement made by artist Julie Gough about the importance of speaking to, and with, a precious object left behind by her Trawlwoolway ancestors, I aim to test if Steyerl’s argument could exist in harmony with an Indigenous orientation towards objects. I’m hopeful her line of reasoning could prove useful in shifting the dominant narratives of mastery, power and force (to borrow Steyerl’s terms) that museums inevitably exert as they translate material cultures. This testing will be done with reference to the National Museum of Australia (NMA) exhibition, *Encounters: Revealing stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander objects from the British Museum, and its companion show, Unsettled: Stories within, where Gough’s statement accompanied her work, Time Keeper* (2015).10 In this way, as I will suggest by way of conclusion, non-Indigenous people and institutions have an opportunity – nay, an urgent need – to learn from Aboriginal epistemologies.

Encounters exhibited 149 Indigenous objects from the British Museum, which were publicly displayed in Australia for the first time since their collection in the colonial period. ‘Collection’ took place in a range of circumstances; from war, murder and exploitation to, in at least one instance, the deliberate gifting of objects by their Indigenous custodian with the specific, and strategic, instruction that they be placed in a major European museum so that the importance and prestige of their original owner could be widely known.11 The collection of objects displayed represents a fraction of the 6000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artefacts the British Museum holds. Encounters follows their exhibition in London, where an originating exhibition was titled Indigenous Australia: Enduring Civilisation.12

All 149 objects displayed are returning to London, despite the objections of many of their ancestral custodians who seek their return. To be fair, the critical debate around repatriation was not suppressed by *Encounters’ installation, which foregrounded – in didactic texts and video interviews – the voices of contemporary Indigenous people, many of whom matter-of-factly requested the return of these objects. That they will return to London despite these objections was just one of many tensions in an exhibition that, visibly at least, wrestled with issues of collection, ownership and meaning-making in the museum. Encounters, which was curated in consultation with the NMA’s Indigenous reference group, primarily sought to address these issues by privileging the living voices of people from the twenty-seven Indigenous communities that were consulted on objects known to hail from their sovereign nations. To an extent, the exhibition sought to position these debates as taking place in the larger context of colonisation. I would qualify this last point, however, by suggesting that the discussion of colonisation’s impact was limited to a historical account. This is not to say Encounters* was not replete with contemporary stories of survival, continuity and endurance, but there was less space for discussion, let alone proposed remedy, of colonisation as a project that continues to unfold in contemporary Australia.

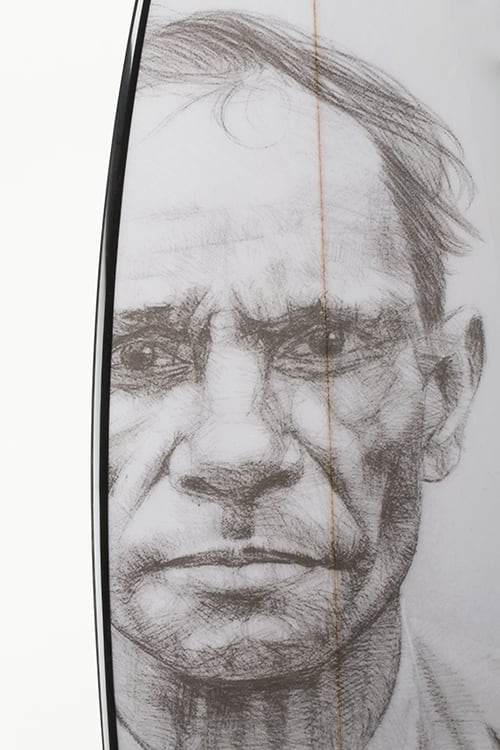

In addition to including contemporary Indigenous voices, Encounters sought to address the problem of ‘interpreting these objects in ways that go beyond simply placing them in a timeless ethnographic past’ by including the work of contemporary practitioners.13 These contemporary objects ranged from utilitarian steel-pronged fishing spears made by Geoffrey ‘Possum’ Clark-Ugle to the exceptional craftsmanship of Girramay weaver Abe Muriata’s bicornual baskets produced in 2012 and a surfboard/shield made by artist Vernon Ah Kee in 2015, as part of his ongoing series cantchant. Bearing Yidinji shield designs on one side, the surfboard featured the image of Ah Kee’s great-grandfather, George Sibley, on the other.14

Alongside these contemporary components of Encounters, literally next-door in the museum, was the exhibition, Unsettled: Stories within, which invited five contemporary artists – Julie Gough, Jonathan Jones, Elma Kris, Wukun Wanambi and Judy Watson – to respond to the themes or specific objects of the larger exhibition. Gough created a sculpture that was in direct conversation with a kelp water carrier, the oldest surviving one from Tasmania, which was exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London before being donated to the British Museum. The vessel was bequeathed to the Museum by Joseph Milligan, the superintendent of the Oyster Cove Aboriginal Station, where, in 1847, 47 Indigenous survivors (of many more) from Wybalenna (Flinders Island) were relocated. These men and women had previously been forcibly relocated to Flinders Island as part of the genocidal ‘clearances’ that took place during Tasmania’s European settlement. Now known as Putalina, Oyster Cove was returned to the Indigenous people of Tasmania in 1995 and Gough is able to say with some certainty that the water carrier in the British Museum was made by one of 23 women – who she begins by naming and recognising in a statement accompanying her work – living at Oyster Cove in those times.15

Gough extends this naming and recognition to the original kelp water carrier, which she describes as a ‘precious object made by our Old People’ and something to enter into reverent conversation with. ‘There was a sense of urgency to communicate with the objects before our time was up,’ she says.^16 ‘I had to let them know we are still out here, waiting for them, remembering them; that they weren’t forgotten.’ Her purpose when visiting this precious thing in London, she says, ‘was to undertake a remaking, a form of sister carrier, with new purpose’.

Creating a metaphor for the urgency of time passing, Gough made a kelp ‘hour glass’, Time Keeper, fashioned in the same ways and materials as the water carrier but through which sand collected at Putalina trickled out to a pile below. ‘Time Keeper is […] a statement about time spent apart – between the carrier, its homeland, its people and its intended purpose,’ explains the artist.^17

Gough’s intentions are in keeping with the non-linear conceptions of time and social structure familiar to many Aboriginal Australians. June Oscar (AO), chief executive officer of the Marninwarntikura Fitzroy Women’s Resource Centre at Fitzroy Crossing and a proud Bunuba woman, delivered a powerful opening address at the British Museum iteration of the exhibition that has since been adapted to an essay in the Encounters catalogue. She writes:

As Aboriginal people, we view the world as cyclical. The concept of knowledgeable voices existing long after death is fundamental to our societal existence. Everything on our country carries the voices of our ancestors: the coolamons, spears and boomerangs; the trees, animals and water sites18

Oscar continues:

There are materials from my people at the British Museum. White men took these from our land and brought it to a foreign place; these materials have names in our language. The trees, stones, grasses still grow and still stand on our lands. These materials sit in a bigger story. They sit at the centre of that story forever. We will never forget this story.19

I want to argue that Indigenous peoples have always had an object-oriented ontology. Where a worldview holds that every rock, tree, kangaroo, bird, river and mountain is alive and capable of communicating with each other we are clearly in the presence of a transversal philosophy. I certainly don’t write this to reassure Indigenous readers that they are up-to-date with fashionable theorisations, rather I would suggest that, as usual, non-Indigenous people have much to gain if they are willing to honestly and openly embrace other epistemologies.20

In her 2006 essay Hito Steyerl, following Walter Benjamin, traces a ‘language of things [that] is mute, it is magical and its medium is material community’.21 For her, the languages of things amount to ‘languages of practice: the language of law, technology, art, the language of music and sculpture’. These material languages must be translated into the language of humans – not any particular human language but one situated in ‘common practice’. This, Steyerl writes, ‘bluntly locates translation at the core of a much more general practical question: how do humans relate to the world?’^22

There is a theistic dimension to Benjamin’s original argument, what Steyerl characterises as the ‘inherently productive’ language of things – Benjamin names foxes, lamps, mountains – which are the condensation of the breath of God Himself in the creation story of the Abrahamic religions. Then, when God created man, he charged him with naming all these things, and human language placed man above and apart from thing and animal, producing the imperative for humankind to, in Steyerl’s words, ‘classify, categorise, fix, and identify’.^23

Steyerl suggests we might map this onto more contemporary, secular understandings of two different spheres: power and force, or, potestas and potentia. She argues that human language can either attempt to engage with the potential of things, with objects’ power taken on their own terms, or through mastery and force. Translation, she says, can be creative or domineering and is most often a mix of each.^24 This resonates with what artist and academic David Garneau, writing in a Canadian Aboriginal context, warns of where translation and the European museum are concerned.25 Garneau writes:

The colonial attitude, including its academic branch, is characterised by a drive to see, to traverse, to know, to translate (to make equivalent), to own, and to exploit. It is based on the belief that everything should be accessible, is ultimately comprehensible, and a potential commodity or resource, or at least something that can be recorded or otherwise saved.^26

Indigenous objects and customary practices are created and disseminated according to precise rules concerning what is secret and what is permissible knowledge, between what is sacred and non-sacred.27 While museums are becoming better at consultation and listening, Garneau points out that ‘[e]xhibitions of Aboriginal art shown within a dominant culture space are always in-formed by the world views of those who manage the resources and the site/sights.’28 He then strategically imagines a number of possibilities for counter-hegemonic ‘sovereign display territories’ where, for example, in an exhibition with roots in an oral culture there might be no written signs or catalogues: visitors’ experiences would be guided at the discretion of Aboriginal knowledge keepers.29

Following a similar rationale, designer and writer John Paul Rangel talks of the Indigenisation of museum spaces whereby First Nations people ‘reclaim a location through cultural signifiers, performance, ceremony, song, dance, or installation that convey the existence and presence of Native peoples and cultures.’30 These may be staged as ‘open’ or ‘closed’ interventions; Indigenous people may choose to let sacred objects know they are being actively remembered through customary ceremonies that are performed away from the eyes of the dominant culture’s curatorial guardians and away from its publics.

Here, however, I would like to invert this argument and suggest that, while Indigenous cultures do have unique relationships to objects and material culture, there are fragments of European thought that also move in this manner and direction. Steyerl writes of the Benjamin dedicated to deciphering modernity through the rubble it leaves behind, the Benjamin for whom:

[…] things are never just inert objects, passive items or lifeless shucks […] they consist of tensions, forces, hidden powers, which keep being exchanged. While this opinion borders on magical thought, according to which things are invested with supernatural powers, it is also a classical materialist one. Because the commodity, too, is not understood as a simple object, but a condensation of social forces.31

While Indigenous objects often (though certainly not always) exist outside the logic of commodities and capitalism, we can see here how non-Indigenous thought might be less classically rational than is often claimed, and, also, how Indigenous thinking might be more rational than European discourses have held it to be. In this view, Indigenous understandings of objects as bearing the living voice of historical social forces and ancestors (both human and non-human) follow a similar logic to that of Marxists and historical materialists who seek to understand their world through the objects embedded in it. Beyond that, of course, the West has its own extra-rational traditions. Alluding to ‘Cree philosophers and Anishinabeg scientists, German mystics and Hungarian witches’, Garneau writes that a:

preference for intellection, for thinking, for scepticism and experimentation is not the genetic inheritance of European peoples alone. […]Reason is not a cultural attribute of the West alone, and spirituality and other forms of extra-rationalism are found in every culture.32

This is not justification for an outmoded fetishisation of the ‘authentic’ and ‘pure’ Indigenous other, where European logocentrism essentialises colonised people by projecting upon them the sensual and non-rational attributes it denies in itself. For Garneau, the teaching that ‘Western-identified persons and institutions should learn from Aboriginal cultures is our emphasis on holism, not the exchange of one partial worldview for another’.^33

European culture urgently needs to learn from Indigenous intellectual traditions. Reviewing Enduring Civilisation at the British Museum, Jonathan Jones – the critic for The Guardian rather than the Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi artist who participated in Unsettled – concluded by emphasising the types of knowledge that have allowed Indigenous Australians to ‘inhabit their lands without wrecking them, to live in nature without wiping it out’.34 He rightly calls that a wisdom the world needs to listen to.

Dylan Rainforth (Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi, Pākehā) is a Melbourne writer. A regular contributor to The Age and Art Guide Australia, among other periodicals, he is currently completing a Master of Arts at Monash University. His research focuses on Hito Steyerl and the political speculations implicit in the contemporary essay film.