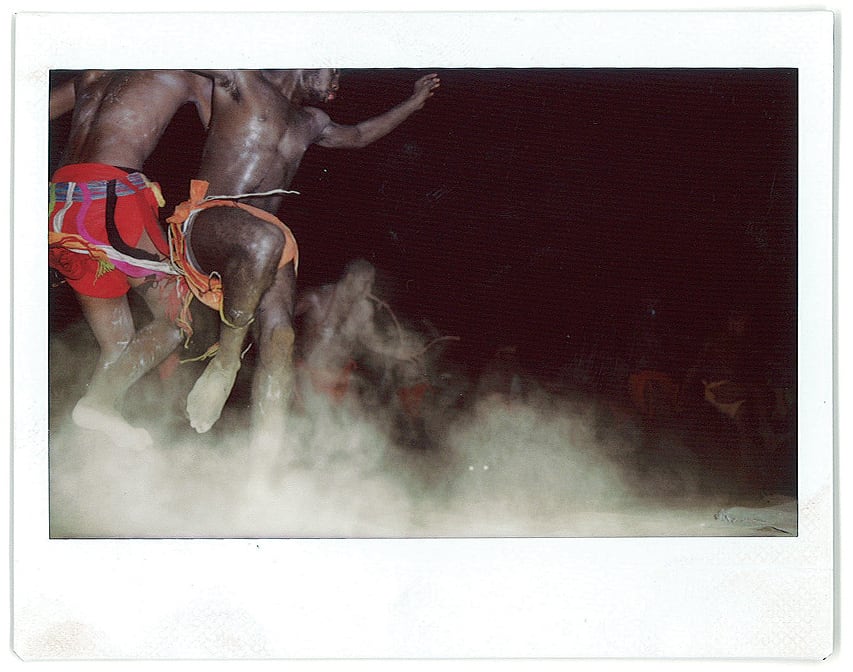

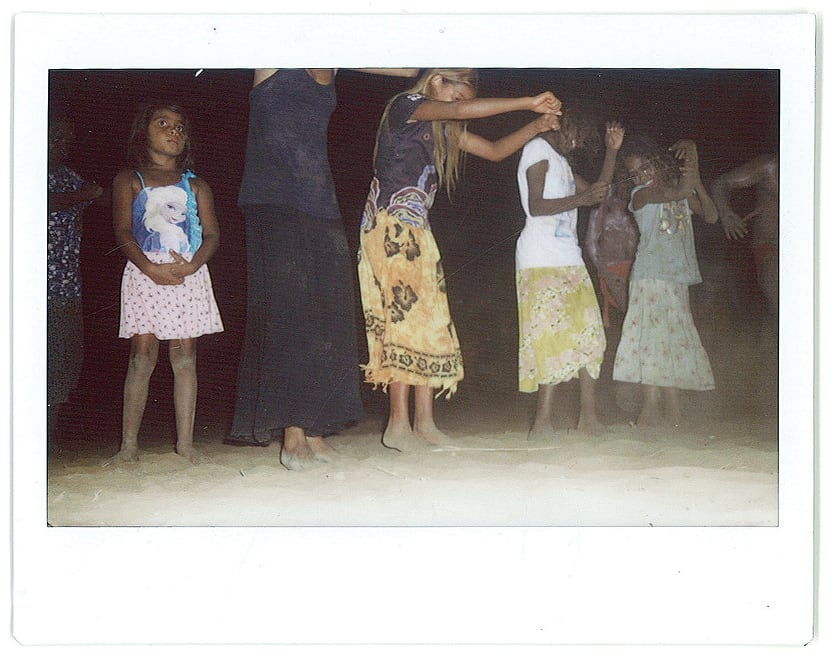

If that dead man might got a son, daughter, grandkid. If he give it to his grandkid or son or daughter, that’s right. But if he can’t give it, well he’ll give that corroboree to another man. That ’nother man might say, ‘Hey, your father been give me corroboree in the night time. Good one too. Well put him on.’ They used to put them on. They used to go for weeks and weeks. Take ’em all over, like a winan.1 This time now, they got a mobile phone or they got a thing to record it, people singing. Well, when they finish singing they go back, they put it on. We fellas learn that way, see. Get that thing on a dvd or video or cassette. Before we used to get it straight out, you know. When people want to get that corroboree or wangga, you gotta take him and show him, sing it bat him,2 and give him a hand to sing him. One water, one tea, two fellas drinking. That’s the way he gets that knowledge from that bloke singing that wangga. By water and tea. When you get a drink from that grandpa, grandpa gammin’ drink that water,3 he drink that water and he wash his mouth, chuck him back la that cup. Spit back in the cup and two fellas drink that water. And all that knowledge go into that little fella. That’s how it used to be, but we don’t do that now.People might ask why we don’t do what my father describes now. We’ve been shifted off our Country too many times, gathered up like bullocks in a yard and forced to live in townships. That’s now our way of life. We’ve drifted away from many of our own traditions and way of doing things. But we still hold on to everything that we can in our hearts and in our minds. And like Dad says although we haven’t shared cups of water or tea for a while, we do have our videos and mobile phone recordings. Recordings of our song and dances spread in our own communities like wild fire. And who knows, maybe this year two fellas, one old and one young, will start drinking from the same cup again.

Chris Griffiths is a Miriwoong/Ngaliwurru man living in the East Kimberley. He is the son of Alan Griffiths, a renowned artist, respected law man and recipient of the 2015 WA State Living Treasure Award.

1. Winan is a traditional form of trade that takes place across different Country.

2. Bat is a Kriol word that changes the verb to mean ‘continuous or habitual’.

[^3]: Gammin’ is a Kriol word that means to pretend or lie about something.