Ry Haskings

Rapa Nui Ranelagh

West Space

2 October – 7 November 2015

Over the last few years, Ry Haskings has presented a number of installations which have utilised the same basic set of ingredients; figurative colour-pencil drawings, colour screen-prints derived from photographic sources, painting, especially geometric abstraction and wall-painting, and building materials and construction techniques that sometimes double as supports for the display of artwork (including ceiling panelling, extruded wall-mounts, extended plinths and steel support poles). Already in this list you get the impression of the interest in a low-key, workaday formality or conventionalism. The works involve and activate this quality in an economical way, which can make them look minimalist, but they never really carry the sense of something ordinary having been elevated — as in purified — or of something profound laid bare. Haskings presents us with generic or functional depictions of the given essentials of certain visual and affective experiences. He stresses the all-round artificiality of artwork by incorporating methodical randomness into its production, by tying his interest in conventionalism to the economy of the work’s manufacture and presentation.

Some of his most successful earlier works concentrate the force of this artificiality into a single point or plane. Like the metres of green, blue and brown diagonal panelling and wall-painting of

Backtrack (AKA Catchfire) (2009), exhibited at the original Utopian Slumps, or

Burros Ballot(2010), whose walled-in construction made the pictorial elements of the work physically difficult to even read. Or the sharp repetition of orange plastic panels that frame morphed colour-grid paintings and doubled-and-overlayed pencil portraits of

Refurbishment life coach (2009). There, the contrast between the physical presence of the work and the domestically severe style help generate disorienting effects. With more recent work, like

The Thirty Cases of Major Zeman (2012) and his PhD exhibition,

Points of Reference (2015), Haskings distributes the attention to artificiality evenly, almost over-cautiously, across the installations. They tend to look like jumbles of highly polished objects, or as though they were assembled by instruction — impressions heightened by the deliberate mis-presentation of a work’s pictorial elements.

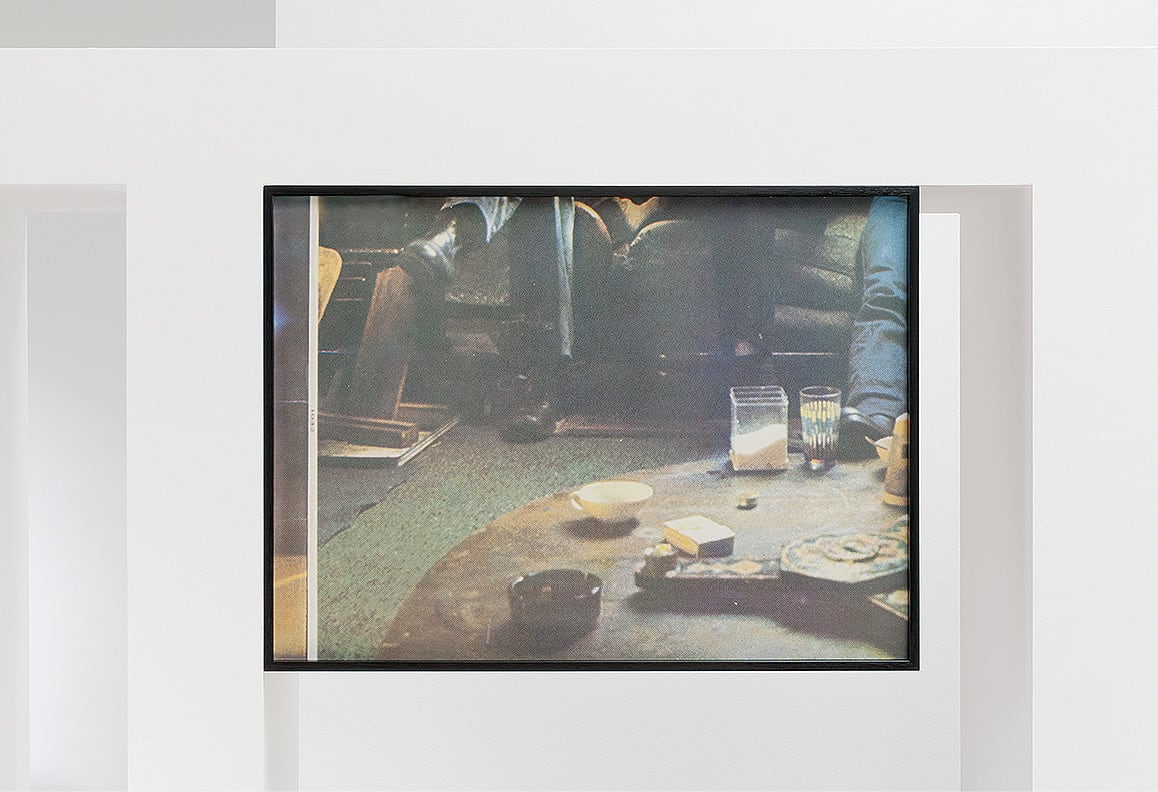

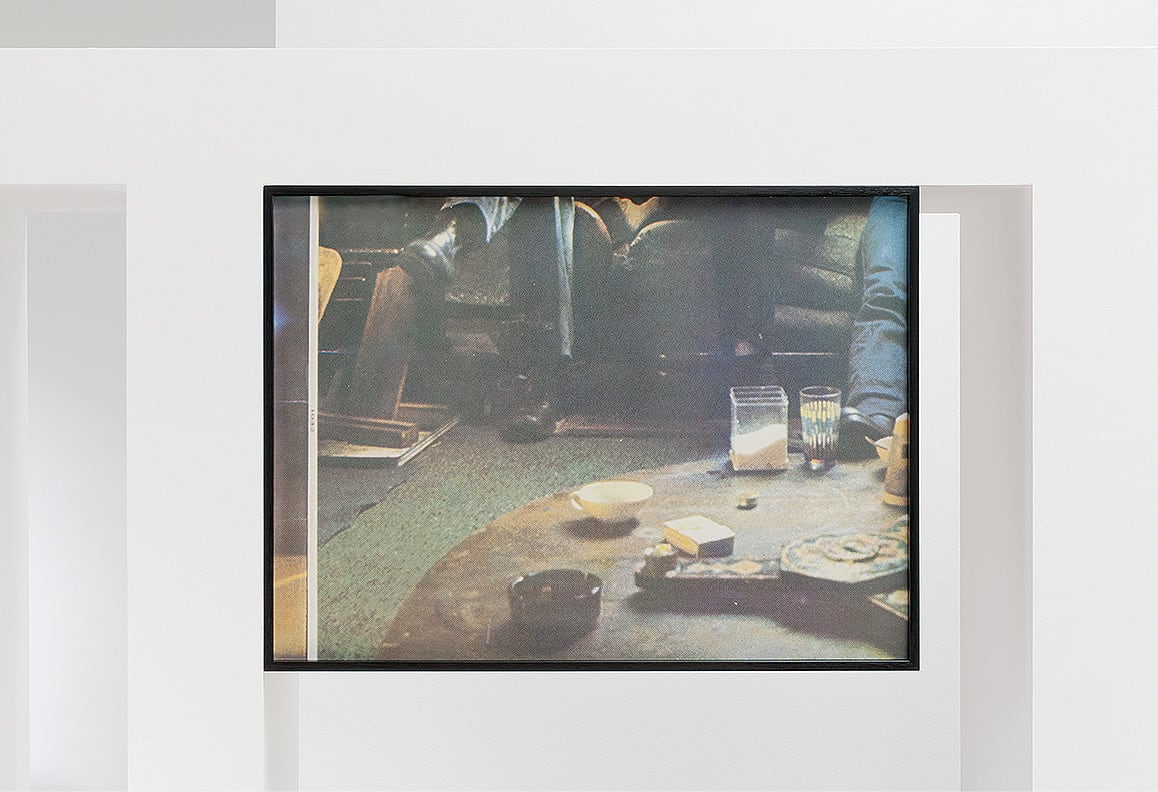

Rapa Nui Ranelagh (2015), exhibited at West Space in October last year, marks a shift towards something softer and more forgiving. The work is based around a perfectly made, over-sized plinth-like table structure, which runs along the entire main wall of the large gallery, and whose seven, unevenly-spaced leg-sections are in keeping with lines drawn by sight from the corrugated concrete ceiling. A second, narrower construction, stands at a right angle to the main piece at the far end of the room. These objects are the display units for a series of images and objects, and this is where the softness comes in: a framed, screen-printed record cover enlargement, hung weirdly from the underside of the smaller of the plinths, shows a 1970s lounge setting. The top half of the sleeve is removed so you can just see the cross-legged poses of band, and the drinks and detritus on the coffee table. A small greyish painting in Constructivist style is hung on another wall-like plinth that extends to the ceiling of the space. This is placed between the two main plinths in a way that makes the painting hard to view, but in an odd or shy, rather than difficult, way. Attached to the base of one of the legs of the main plinth is a washed-orange screen print, taken from a photograph of an old church lectern. And placed on top, leaning against an exposed plumbing line, is a large aluminium panel, which has a broken door-latch fastened to it in its own cut-away section.

Rapa Nui Ranelagh seems ready to defer to the empty authority of style and composition, but combines the new approach with the balance between slightness and hulking physical presence of older works. The subtle continuities between the pristine constructions, the images, their uninterpretable content, and the physical features of the gallery space blend together into the one resonant, off-kilter, meaningless moment.

This work is not abstract, but it is disposed towards the generic characteristics of generic things. If it is an affirmation of that artificiality, it can still feel tinged by a kind of wariness, the sense of something having to be held in check. Haskings’ practice suggests a way of articulating the dilemmas facing art as a medium of communication. For example, in abstraction, where abstract forms are supposed to behave as the vehicles for some greater purpose — in order to raise the level of thinking about perception, or if they are turned against modernist ideologies of progress — then the forms are taken as means. But this grants them a reality that from this perspective is open to question. There is a lot, maybe too much, assumed in the idea of form. If the communicability of form can be put into question when you recognise that these fundamental categories are just convention, the idea that art could be a vehicle for anything at all is already in doubt.

Michael Ascroft is an arts writer based in Melbourne.