Imagine yourself strolling into a gallery. You pause at the entry to read the introductory wall text but find yourself struggling to see much over the shoulders of other patrons. Rather than stand on tiptoes, you use your phone to scan the QR code pasted on the wall. You are instantly taken to a page on the artist’s website displaying a précis for the current exhibition. After reading this you browse the site, eventually landing on the artist’s bio and previous exhibitions. Looking up from your phone, you find yourself in the first room of the exhibition proper, where you recognise a work from the publicity campaign. As you stop to take a closer look, the gallery app recognises your location and offers you a short commentary on the work written by one of the exhibition’s curators. You decide you like the piece, take a quick photograph and upload it to Instagram before moving on. Wandering through the remaining rooms your attention flits between the app and the works themselves. On your way out you skip the bank of touchscreens in the education space, figuring that you have already read most of the content on your phone. A gallery attendant at the exit tells you about the artist’s keynote lecture, which is now available via video streaming on the gallery’s website. Afterwards, on a tram on your way home, you pull up the lecture on your phone and dutifully log the details of your visit on the app.

The above scenario is not intended to parody the uses of digital media in the contemporary gallery, but to emphasise how technology is transforming the way we experience galleries and the artworks therein. In today’s gallery – once a sanctuary of whispers, softly shuffling feet and postures of contemplative repose – we are bombarded with information from every direction. No longer a sacred refuge from the white noise of everyday life, the gallery is merely another node in the voluble flow of information across the planet. Indeed, the mediating presence of digital technology might be said to be characteristic of today’s gallery-going experience.

It is not easy to assess the effects of this omnipresent, but often unnoticed, veil of mediation. Are we distracted by such technologies; our embodied experience of an exhibition attenuated as our mind wanders with our devices? Does the glut of digital content over-determine our encounter with the artwork, subliminally moulding our responses ahead of time? Or are these exciting new democratic avenues of engagement enriching our experience, refashioning our mode of participation and stimulating us to think longer, harder and in new ways about the art we are encountering?

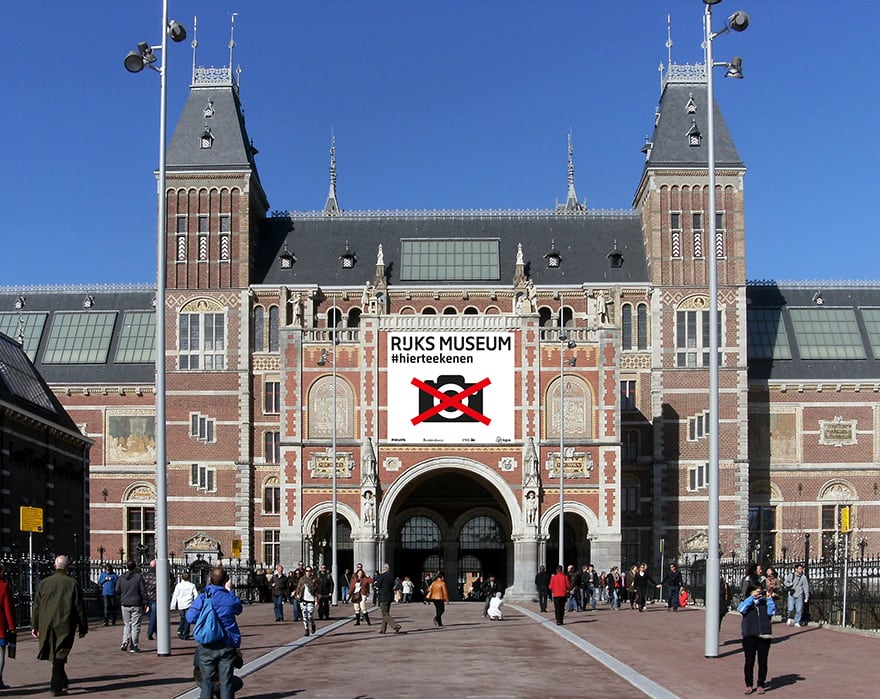

Management at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam have come down firmly on one side of this debate. That august repository of masterpieces by Rembrandt, Vermeer and Hals recently implemented a program to discourage visitors from using phones and cameras, asserting that:

In today’s world of mobile phones and media, a visit to a museum is often a passive and superficial experience. Visitors are easily distracted and do not truly experience beauty, magic and wonder. This is why the Rijksmuseum wants to help visitors discover and appreciate the beauty of art and history through drawing, so #startdrawing!1

Ignoring for a moment its paternalistic and slightly elitist rhetoric, this passage is fascinating for its internal inconsistencies: symptoms of a tension between ideology and marketing, elitism and egalitarianism. The Rijksmuseum has implemented a host of measures aimed at seducing visitors away from their smartphones and into analogue gallery time: there are drawing tours, drawing assignments, a drawing picnic room and the free provision of sketchbooks and pencils. What is largely absent, however, is any justification for the institution’s prioritisation of the non-digital mode of engagement (drawing) over the digital (crafting an Instagram photo). Why does the former necessarily constitute a deeper or more worthwhile engagement with the artwork than the latter?

Similarly absent is any consistency in the museum’s eschewal of digital media. On the one hand commanding that you put your phone away and draw, and on the other engaging in a saturating digital marketing campaign to promote the #startdrawing program - featuring videos on the Rijksmuseum YouTube channel, a Facebook page, sketch animations, a blog, an email newsletter, Instagram, Twitter and the eponymous hashtag. Judging by the uptake on all of these mediums, the program has been highly successful in encouraging people to spend extended periods with the artworks. This success is, at least partially, attributable to the desire not just to draw, but also to digitally capture and instantly publish one’s drawing. So a campaign that ostensibly wants to get people off their phones has to resort to the very forms of digital mediation against which it rails.

In its attempt to retreat to an antediluvian analogue time, the Rijksmusuem inadvertently confirmed the impossibility of any such retreat. The museum’s mistake was to target cameras and phones as the creators of distraction and passivity, when they are simply the latest conduits for it. Digital technology should not be conceived of as the enemy, yet some institutions cast it as such because of the threat it poses to their sovereign control over what happens in the gallery space. Digital media academic, Ross Parry, argues that museums can tap into this diffuse digital energy, with the contemporary museum becoming postdigital.2 That is, digital mediation should not function as an autonomous domain, but rather should be ‘blended and embedded’ in the very fabric of the museum, negating ‘neat distinctions between “digital” and “nondigital”’.3 If, as Parry contends, we are reaching a tipping point in the adoption of new media, with technology becoming normative in the museum space, then both gallery management and patrons must attend to the ways these technologies are shaping our experience of the gallery visit.

One way to think constructively about these issues is by turning back to the pre-digital age of Walter Benjamin, whose conception of the ‘aura’ of the art object remains the definitive statement on the effect of viewing physical works of art in person. Benjamin writes:

Even the most perfect reproduction of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be…the quality of its presence is always depreciated…that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art.4

For Benjamin, the aura of an artwork encompasses its authenticity, authority, and role as repository of historical testimony. The withering of the aura brought about by mechanical reproduction diminishes these constituent elements. Freed from the auratic chains of passivity and submission, the viewer adopts a new relation to the art object, becoming the possessor of a ‘perception whose sense of the universal equality of things has increased’.5 In the vacuum left by the destruction of the hierarchical relation lies the space for new thought to unfold. Benjamin sees in this the possibility of art reconfiguring our perception of the world, functioning as both a critique and a hope, leading us towards emancipation from present conditions.

Reading Benjamin today, one cannot help but be struck by the correspondences between his account of an artwork’s mechanical reproducibility, and the fears and hopes that surround digital mediation of artwork in the contemporary gallery. Both phenomena proliferate reproductions, impose and disrupt meaning, and influence the terms of our engagement with art. Might it be then that digital technologies are capable of fulfilling the project started by mechanical reproduction? Can the iPhone emancipate us from the strictures of the conventional gallery, thus rendering the space more democratic and conducive to emancipatory or radical thought?

This may be the case, but it is certainly not as simple as transposing Benjamin’s theory of mechanical reproduction onto today’s postdigital world. As the contemporary critic, David Joselit, notes, ‘Benjamin’s essay can hardly account for the revolutions in image production and circulation [initiated by digital technologies]’.6 Elsewhere he explains:

What makes our present moment distinctive is the degree to which devices such as the iPod, the cell phone, and the personal computer allow our bodies to occupy two places at once … This experience of straddling two or more locations simultaneously has caused the negotiation of both physical and virtual worlds to become increasingly disembodied.7

The most frequent forms of digital mediation present in the gallery – the museum app, the audio guide and the touchscreen – initiate this disembodiment, effecting a confusion between the physical and virtual planes that is liable to lead to distraction. While the material form of digital mediation may mobilise a bodily displacement, their discursive expressions also have the potential to rupture a productive engagement with the art. For the content of these digital platforms is commonly directed towards fulfilling a meaning-oriented pedagogical function. Generated and proliferated from the authoritative subject position of the curator or the critic, this content re-constitutes the meaning that Benjamin hoped might be sundered by reproduction, thereby binding the viewer to prescribed meanings conceived by and within existing power structures.

This is not to say that institutionally-endorsed digital technologies cannot frame the sort of artistic encounters that Benjamin hoped for. The ‘O’ at MONA and the ‘Pen’ at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum provide interesting case studies. MONA’s O infamously permits gallery visitors to vote against their least favourite artworks, the premise being that if enough people voted against a work that piece would be replaced. The O’s content delivery tends towards the playful as opposed to the didactic. At the Cooper Hewitt, the Pen, a piece of visitor technology which provides information but also allows for individual creativity, is born out of the museum’s philosophy of collaboration and play. The Pen allows individual visitors to curate their own collections of design objects and also design their own objects, all of which is subsequently accessible on the visitors’ own unique web address, printed on their ticket. While at first glance these innovations seem to conform to a flattening of the artwork-viewer hierarchy, the more burning question of whether they carve out a space for new thought is, at best, uncertain. After all, these devices and programs must answer to multiple demands, including marketability, accessibility, practicality and cost; on occasion the satisfaction of these competing interests will impoverish, rather than enrich, the viewing experience. Anyone who has been to MONA and seen the number of visitors with eyes glued to their O will understand how powerfully this tension between distracting entertainment and meaningful engagement can manifest itself in the gallery space.

At a time when galleries operate along quantifiable rubrics like ‘dwelling time’, ‘repeat visitation likelihood’, and ‘post-visit login percentage’, the gamification of digital mediation and the concomitant sustained distraction generates a lucrative revenue stream. Museums and galleries are not outside the paradigms of economic rationalisation and they too are being propelled towards superficial, accessible and time-poor avenues of engagement in order to ensure the maximum flow of traffic through their doors and portals. Any hopes that galleries will harness digital technology to operate along qualitative rubrics consisting of thought, praxis, and emancipation seems naively utopic and may go the same way as Benjamin’s hopes for revolutionary film, trampled under the wheels of capitalism.

But there are glimmers of hope, points at which market imperatives coincide with democratic values and innovation impulses. Think, for example, of the various technologies – both institutionally endorsed and independent – cropping up around the world that allow people to visit galleries virtually or remotely: the Google Art Project, telepresence robots, virtual tours, and the countless hours of bootleg and home video of exhibitions available online via YouTube, Vimeo and various blogs. Whilst the motivations driving the generation and proliferation of these technologies differ markedly, they all have the same potential to open up vast quantities of art to people who otherwise would not be able to access it by reason of infirmity, geographic remoteness, physical disability or financial hardship. Think, too, of the advent of computer-aided design, 3D scanning and printing. This technology is being used by organisations like Factum Arte to document, preserve and recreate endangered artworks and artefacts, as in the case of their one-to-one facsimiles of Tutankhamun’s tomb and Veronese’s Wedding at Cana. Rudimentary versions of the same technology are available to anyone with a smartphone, allowing the so-inclined gallery visitor to surreptitiously scan her favourite Rodin or Koons and send the file off to any of a burgeoning number of large-scale and boutique 3D printing services. It remains to be seen, though, whether these innovations will become truly accessible and emancipatory or just another frontier of the commodification of our consumption of art.

Matthew Taft is a PhD student in the English department at Duke University, North Carolina.

Julian R. Murphy is a lawyer currently living in Melbourne.