Everything Falls Apart

Part I: Alessandro Balteo Yazbeck & Media Farzin, Jem Cohen, Phil Collins, Sarah Goffman, Sarah Morris

Part II: Vernon Ah Kee, Zanny Begg & Oliver Ressler, Jem Cohen, Tony Garifalakis, Merata Mita

Curated by Blair French and Mark Feary

Artspace, Sydney

Part I: 27 June – 5 August 2012

Part II: 10 August – 16 September 2012

After a partnership of almost two decades it was a surprise to see that Sydney’s Artspace would not be a presentation partner for the 18th Biennale of Sydney. Despite the Biennale’s theme of all our relations, the relationship between the two organisations was placed on hiatus as punters flocked instead to the post-industrial playground of Cockatoo Island in record numbers. This allowed Artspace’s Executive Director, Blair French and Curator, Mark Feary to take advantage of the opportunity to place their programming in inevitable, if not intentional, comparison across concurrent exhibition dates. Conceived and presented as a two-part exhibition model, Everything Falls Apart provided a thorny counterpoint to the Biennale’s apparent distaste for separation, negativity and disruption as intellectual and emotional prisms from which to view the state of the world today — itself a hugely imprecise subject of study, for which everyone and no-one knows something about. Significantly, it did this not by means of literalist opposition to the premise of universal solidarity, but instead by effectively proposing that the problem may in fact be the very constituent of our relationships: the cocooning, confining and confounding spaces of diplomacy. When forced to make concessions, accommodate unfamiliar faces or simply get squeezed—and hard!—the brave jump up and shout. This reaction to the python grip of provocation separates the individual from the huddle. Taking its title from the 1983 song and album by American punk band Hüsker Dü, Everything Falls Apart probed contradictory desires of rejecting and accepting the status quo, explicit in punk rock’s ethos, by offering works that placed dispute and confrontation as an a priori structural determinant of human interaction—if one person is splendid isolation, then two is a dispute waiting to happen.

Part I foregrounded the curators’ proposition of examining the actual, imagined and desired collapse of ideological and political systems by presenting a suite of works that conceptually conjoined historical and contemporary reflections on the pressuring forces of social and political upheaval, as Kafka memorably put it, ‘every revolution evaporates and leaves behind only the slime of a new bureaucracy’. It is perhaps an inflexible frame through which most of us view our place in the political paradigm today — being, as we are, largely disassociated from the decisions of the powerful, who themselves seem ruled by abstracted, inhuman bodies of authority, such as the corporation. Such a frame might explain how one views Phil Collins’ masterful double-header films, marxism today (prologue) 2010 and use! value! exchange! 2010 with a misplaced sentimental pensiveness for the German Democratic Republic’s foundational myths. Pulling up a small, chipped wooden chair at a desk, as if settling into class, I sat mesmerised by a teacher who, with impressive clarity and verve, elucidates Marx’s principle of surplus value to a class of undergraduate students in Berlin. Marx’s dictum ‘all that is solid melts into air’ is deliciously evoked as one becomes engrossed in Collins’ poetic document of the personal stories of former teachers of Marxism–Leninism, whose profession became irrevocably and spiritually bankrupt following the turning tides of history once state socialism collapsed in East Germany. This is juxtaposed with archival footage from the 1960s and set to a hypnotic soundtrack. Considered in relation to the screening of fellow UK artist Sarah Morris’ 1972 2008, a journey into one mind’s ruminations over the implications of the terrorist massacre of Israeli nationals during the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, the emphasis on the psychogeography of the German experience in the twentieth century remains a significant thread with contemporary resonances.

Of less powerful authorial vision was Berlin-based Venezuelan artist Alessandro Balteo’s collaboration with New York-based curator Media Farzin, Chronoscope, 1951, 11pm 2009–11, which under utilises recordings of a CBS news program in the early years of television. The qualitative level of their method of appropriation of original sources—a cut and paste of conversations between a cast of political commentators—seems inadequate given the inherent interest and significance of meaning in historical documents whose raw power trumps the artists’ didactic use of the material. Watching this work to come away with an impression that, yes indeed, the UK and USA intervened in Iran in 1953 to guarantee their exploitation of her sovereign oil is to recall Susan Sontag’s supposition that ‘photography transforms reality into a tautology: when Cartier-Bresson goes to China, he shows that there are people in China, and that they are Chinese’. In this sense, the artists offer answers to questions hardly worth asking due, surely, to their self-evidence. Of some disappointment, too, was Sydney artist Sarah Goffman’s Occupy Sydney 2011–12, more than one hundred, wall-mounted black marker on cardboard placards that can reasonably be interpreted as either an exercise in the process by which museums deaden the raw demands of the streets or, conversely, as a sardonic paean to the pie-in-the-sky idealism of protestors. Either way, the work’s drab aesthetic presence worked against any desire for further intellectual engagement.

In Everything Falls Apart: Part II the emphasis was on the particularities of conflict in cause, context and consequence, which was rather apt to think about given my visit to the gallery took place the day after the recent violent Muslim protests in downtown Sydney. Vernon Ah Kee’s installation Tall Man 2010 utilises video footage from community and CCTV sources documenting the social upheaval on Palm Island in 2004. The artist’s confronting stop/start edits between viewpoints and moments of reason and violence successfully places the viewer in the unsettling position of having to negotiate with the unfolding of uncertainty, and the spring-coiled tension, that can exist within all of us, between passionate involvement and detached observation. Conversely, in What Would it Mean to Win? 2008, Zanny Begg and Oliver Ressler present scenes of protest and blockade at the G8 Summit held in Heiligendamm, Germany, interspersed with vox pops with the protestors, who seem too accustomed to asking nicely for things — conflict vs. manners. ‘Resistance is also something that is joyful, that people can come together and celebrate’ chirps one of the protestors, sounding a lot like someone who can afford to wait their turn.

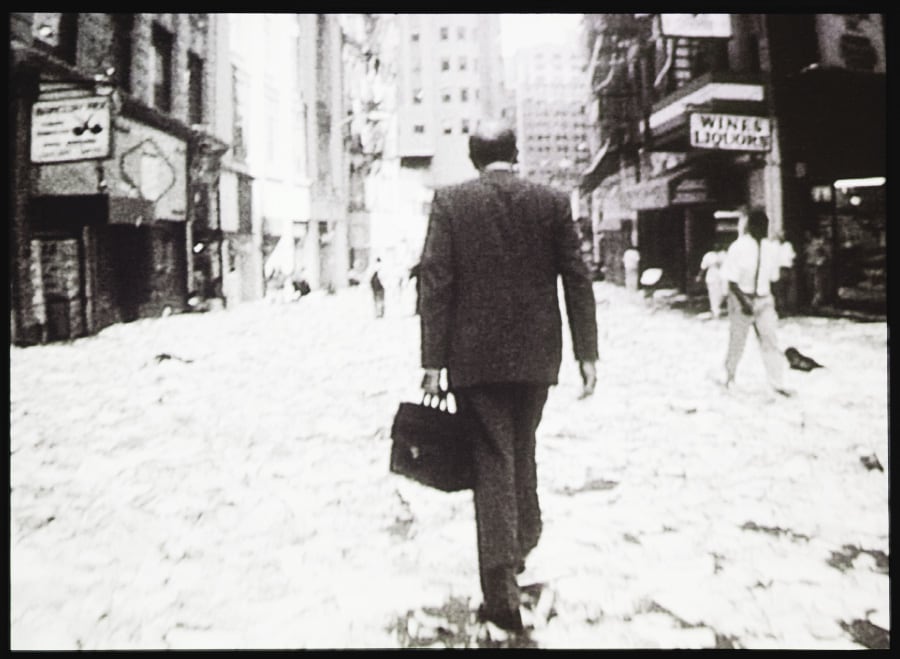

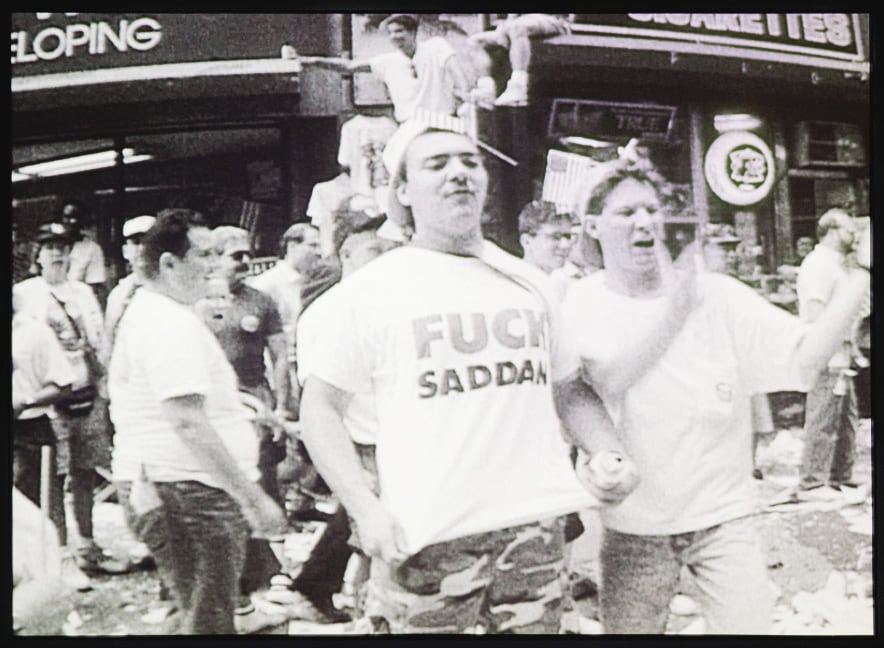

Tony Garifalakis’ series of Affirmations 2012, poster-sized stock images of American law enforcement targets overlaid with the positive affirmations of the motivational therapist, were strangely foreign to my eyes. This was not because our culture lacks violence but because, thankfully, it’s one that doesn’t include guns in the firsthand experience of most people. While visually arresting, the work lacked a convincing anchoring point in lived experience when viewed in an Australian context. The standout work in Part II was Jem Cohen’s Little Flags 1992–2000, which was significantly more inspiring than the inclusion of his Gravity Hill Newsreels 2011–12 in Part I, the latter depicting goings-on around the fringes of the central sites of the recent Occupy Wall Street protests. In Part II, a haunting short monochromatic film places us within the eye of a tornado of celebration and patriotic fervour in downtown Manhattan during the ticker-tape reception of troops returning from the 1992 Gulf War. Little Flags displays a brilliant visual eloquence, sharpened by the shock of 9/11 — an event unforeseen at the time — that drives home a valuable lesson of history that is perhaps also a parable of artistic creation: victory is never wholly victorious, defeat is rarely defeating.

Pedro de Almeida is Program Manager at 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art and a regular contributor to Art & Australia, Art Monthly Australia and other publications.