Few artists are independent. Almost all rely on or seek support of some kind. There are, however, certain artists that require particular types of support. In 2010 I became involved in a project called the Supported Studios Network (SSN). The working group that maintains the project consists mostly of artists who work within visual arts studios that support the professional development of differently-abled artists. These institutions are called, unsurprisingly, ‘supported studios’. The SSN has numerous aims and objectives, all of which pivot around the belief that ‘supported artists’ are able to contribute meaningfully to cultural production in Australia and therefore should have access to development opportunities in all aspects of professionalised art making.

The False Economy of Outsider Art

Efforts to professionalise the supported artist are necessary to counter the historical positioning of differently-abled artists within non-professional contexts. Such artists are often seen as practicing within a psychological or health framework — art therapy — in which art making is a method rather than a cultural form. Alternatively they are included in the dubious category of ‘outsider art’, whereby they become fetishised as practitioners allegedly operating beyond the despoiling influence of commercial or professional concerns. In Outsider Art: Spontaneous Alternatives, Colin Rhodes describes the outsider artist in such terms as to place them beyond the reach of professionalisation:

The desire to make images and to communicate something of the otherwise unsayable is innate in all of us… A few people become professional makers of images or spectacle, that is artists in the modern western sense. But there is also a rich and varied group of creators who did not fit into the official category of the professional artist, however it is defined.1

Outsider art is an outdated method for framing non-normative cultural production. The implication of Rhodes’ use of past tense in his description of the outsider archetype suggests such designations are relevant to art history, but not contemporary practice. Despite this, supported studios often promote their artists as outsiders, either because curators and other artists have suggested this term for their artists, or to access a market through which to sell work and continue supporting their artists. It takes only a cursory survey of the outsider art market in Australia to realise that this is shortsighted and delusional, not least because the market is small and unlikely to grow, but also because the concept of a professionalised outsider artist is a contradiction in terms.

Within the theoretical confines of outsider art there is no room for an artist’s participation in any non-art-making activities associated with a professionalised practice, such as formal training, networking, discussion, promotion and association with artistic networks. To apply the label of outsider to an artist on their behalf is to ghettoise them within a narrow and unbending market not equipped to sustain professional practices.

The Apparitional Mainstream

Even when studios eschew outsider art as a mechanism to professionally develop their artists, what often remains as a rallying point is a common and highly developed awareness of these artists’ perceived marginalisation from the so-called ‘mainstream’ art world.

Studio ARTES, a northern Sydney studio, recently held a panel discussion on this topic at Sydney College of the Arts as part of a symposium focused on supported studios, assisted by a grant from the National Association for the Visual Arts (NAVA). One panel member representing a Sydney artist-run initiative made it clear that, while he would normally object to being cast as representing the ‘mainstream’, in the context of the panel he would make an exception. The participant’s willingness to sublimate his discomfort with the term ‘mainstream’ is emblematic of current tendencies surrounding work to professionalise supported artists. To some degree it has become the norm to describe this work as being primarily the act of integrating the supported artist with an apparitional mainstream, while simultaneously pushing aside concerns about the equivocality of that term.

Adam Geczy describes the art world as it exists within contemporaneity as a ‘system of fluid and constantly redefining demarcations’ and argues that ‘there have always been outsides to art, and these outsides are multiple and exist according to many categories’.2 Geczy’s view is paralleled by Rhodes, who describes this world as a ‘complex set of dynamic relationships’ amongst artists and institutions, and furthered by Hans Belting, who, in equating contemporary art with the concept of ‘global’ art, elucidates a model most readily defined by its lack of definition:

Art on a global scale does not imply an inherent aesthetic quality which could be identified as such, nor a global concept of what is to be regarded as art…it indicates a loss of context or focus and includes its own contradiction by implying the counter movement of regionalism and tribalisation.3

This view seemingly destabilises sector-based projects, such as the SSN, by suggesting that there is, theoretically, no definable supported studio sector for them to represent. Simultaneously, it illuminates professionalisation — supported or not — as being a subjective and highly individualised process with no common beginning, pathway or end. Such a process is not a strategic project or industry trend but rather an endless series of projects undertaken on an artist-by-artist basis within the detribalised and interwoven network of individual artists and institutions that Belting, Rhodes and Geczy describe.

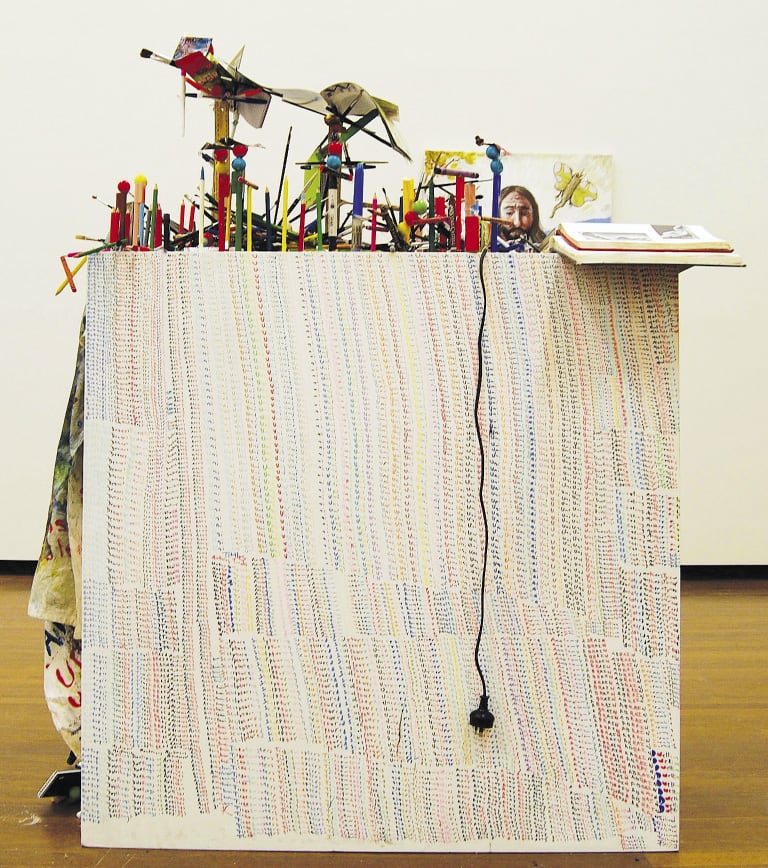

How this plays out in real terms can be demonstrated by the recent Studio ARTES project, Studio ARTISTS Collaborate. Through this project a number of supported artists were paired with practicing professional artists relevant within their discipline. For example, supported artist Robert Smith was paired with installation artist Alison Clouston. Smith produces work prolifically, predominately by drawing masses of small portraits on any paper he can access. On a material level his practice is basic; however its simplicity obscures the complex emotional processes and layers of meaning that his process represents. Clouston’s role in the project was not to advise Smith on technical matters, but to assist him in refining the complexities of his process into something communicable through installation and video work. Meanwhile, Matthew Calandra was mentored by Michael Kempson, artist and director of Cicada Press at the College of Fine Arts. Unlike Clouston, Kempson’s role was not to assist in the development of the conceptual basis for Calandra’s work, but to expose him to new and more complex production techniques than he had experienced in the supported studio, as well as a network of like-minded artists.

A key factor in the project’s success was its facilitation by studio staff possessing in-depth understanding of each artist’s individual practice, the multiplicity of artistic networks operating within Sydney and, most importantly, which of these networks offered the best professional opportunities to the artists.

Critical Distance and the Art of Talking

What other non-art-making skills are required of a professionalised artist? Rhodes repeatedly argues that, in order to operate professionally within the cut and thrust of the art world, however it is defined, an artist is ‘not least expected to talk: to other artists, to dealers, critics, curators, and to collectors, about art’ and to be seen as doing so.4 Besides simply supporting the expansion of professional networks, this act of speaking allows an artist to communicate a rationale for their presence within the networks they seek to operate within. There are innumerable ideas, critical theories or points of view available to the artist for this purpose, however none can be deployed convincingly without evident application of critical distance, a process requiring engagement with art at a theoretical level.

It is often the case that supported artists do not discuss their work with other artists, collectors, curators, writers or dealers. This may be because they are unable to access opportunities to do so, because they are not interested in doing so or, in some cases, because they are simply unable to do so. Networking and integration into any community can be difficult for the supported artist, but this is especially true of contemporary art communities, as they are mostly based in the inner city, while supported studios are often (though not always) located in suburban or regional areas. These include: Project Insideout in the northern Sydney suburb of North Ryde, NSW, or Art Unlimited in Geelong, Victoria. Where studios are located in more central locations, such as Arts Project Australia in Northcote, Victoria, or Roomies in Marrickville, NSW, they tend to enjoy a noticeably higher profile among contemporary art networks.

If the supported artist is unable or unwilling to talk about their work or that of others at a theoretical level, and be seen as doing so, does this immediately disqualify them from opportunities to professionalise their practice? Is it possible or acceptable for an artist to develop a professional practice by allowing others to apply critical distance to the work on their behalf? Can the support of a studio extend this far?

Frédéric Bruly Bouabré: The Scaffolded International Artist

Ivorian artist Frédéric Bruly Bouabré has been prolifically producing work since the 1970s. His work explores a number of ideas including the documentation of his own visions, which began in 1948, and the modest task of drawing together all the knowledge of the world in a single work.

Bouabré’s professional career as an artist began with his inclusion in the landmark exhibition Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of the Earth), curated by Jean-Hubert Martin and displayed at the Pompidou Centre, Paris, in 1989. Since that exhibition, Bouabré has gone on to participate in solo and group exhibitions at reputable galleries in the UK, Spain, France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Japan and Sweden, and in Australia as part of the Gallery of Modern Art’s 21st Century: Art in the First Decade.

In a review of a Bouabré retrospective at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery in 2007, critic Richard Dorment justifies Bouabré’s practice for him by applying critical analysis to the work and stating unequivocally that it is derived from a professionalised practice.

Bouabré more than holds his own. I can’t say this exhibition transforms him into a major artist, but then I’m sure Bouabré doesn’t give much consideration to those kinds of labels. What is important is that after seeing this show you could never categorise his work as either folk art or outsider art, as I had feared.5

As far as I am aware Bouabré does not work out of a supported studio, but neither is he visibly active as a professional artist beyond the production of his work. There is no evidence of him engaging with art (either his own or that of other artists) at a theoretical level, actively promoting himself as an artist or desiring formal training. Yet, somehow he has managed to develop and maintain a high-profile international practice as a professional artist, including exhibiting his work at the Bilbao Guggenheim and the Tate Modern.

The Intimidating Long-view

There are many supported artists who, at the very least, according to the guidelines set out by NAVA,6 can be considered professional artists. John Demos is a supported artist whose work explores complex systems such as science, mathematics and language. He has received formal training, exhibits regularly, offers work for sale, has received grants and undertakes residencies, and he has done all of these things with support and guidance from the coordinator of the Project Insideout studio at Macquarie Hospital.

If the fluidity of visual arts networks can accommodate artists such as Demos and Bouabré, and it is acceptable for them to professionalise with the support of a third party, then theoretically all that remains is to ensure that the structure that supports them is able to do so over the course of a career. This cannot be achieved without significant long-term funding. When considered with this intimidating long-term view, it becomes apparent that the appropriate function of a group such as the Supported Studios Network is not to professionalise the supported artist, but to assist the supported studio in identifying sustainable income streams and methods for providing continual support to their artists. In other words, it is our job to do what all other representative bodies seek to do: build a better, stronger scaffold capable of providing safety and structure to professionals working in an uncertain industry.

Hugh Nichols is a Sydney-based arts, culture and music writer.