Vivienne Binns

Vivienne Binns: Art and Life

Curated by Dr Penny Peckham

Latrobe University Museum of Art, Melbourne

2 July – 24 August 2012

Some exhibitions allow you to realise that there are gaps in the discourse we conduct about contemporary art. In the introduction to the catalogue published to accompany the exhibition Vivienne Binns: Art & Life at LUMA, Dr Vincent Alessi acknowledges Binns’ position at the forefront of several movements in Australian contemporary art, including feminism and community arts. Given our recent focus in Australia on relational, politically or community orientated arts practice, on the legacy of conceptualism and feminism, it’s curious that the practice of an artist like Binns is not more prominent in the conversation.

This is a smallish exhibition presenting some twenty-one works. Major projects from Binns’ practice are represented: the feminist-influenced Experiments in Vitreous Enamel 1976; paintings and mixed media works employing Tapa patterns from Polynesia, and an ongoing series of paintings referencing patterns sourced from borrowed, found and gifted items. Significantly, Binns’ early paintings — including those from her first solo exhibition in 1967 and her more recent collaborations with other artists — are not included in this exhibition, nor are her community projects, collaborations with former pupils Geoff Newton and Derek O’Connor, or works from the 1980s. Despite the modest scale of the exhibition, curator Dr Penny Peckham succeeds in providing an introduction to the breadth and depth of Binns’ oeuvre and an insight into the ongoing development of her practice.

Vincent Alessi points out that Binns has ‘welcomed collaboration as much as she has purposely mediated a singular practice’,1 and that the exhibition shows the artist addressing the question of self and place whilst ‘navigating the art historical canon, not only trying to find a place within it but questioning its modes of operation and construction’.^2 If we are to consider why Binns’ work is apparently in the background when we think about Australian art, the key concept is her eschewal of singularity in favour or the multiple, the various and the many.

Many artists working with feminist concerns during the 1970s produced personal or biographical works emphasising the multiple roles played by women in society, contesting the idea that significant lives chart a singular trajectory. The earliest works in the exhibition are enamelled works from the exhibition Experiments in Vitreous Enamel: Silk screened portraits of women 1976. This exhibition was produced by Binns working in collaboration with three other artists — Marie McMahon, Toni Robertson and Francis Budden. Each artist used images sourced from their family’s photo albums to create images of mothers, sisters, female relatives and friends in a more nuanced way: ‘as people’, rather than just mothers or sisters. At the time, the artists’ choice to work collaboratively, and to use media and processes associated with ‘applied’ rather than ‘fine’ arts, mark this project as one approached using a conscious feminist strategy.

See That My Grave’s Kept Green 1976 juxtaposes an image of a female relative seated next to a piano — a typical image of a middle- or working-class woman from the nineteenth century — with an image of Binns singing during a performance at Watter’s Gallery, 1972. The act of making music — a creative act as well as a cosily social one — links the mother and the artist; in placing these images together on the same plane, Binns created an image that opposes orthodox views of culture and value, consciously projecting an image of herself into the world as both an artist and a daughter in the lineage of cultural production.

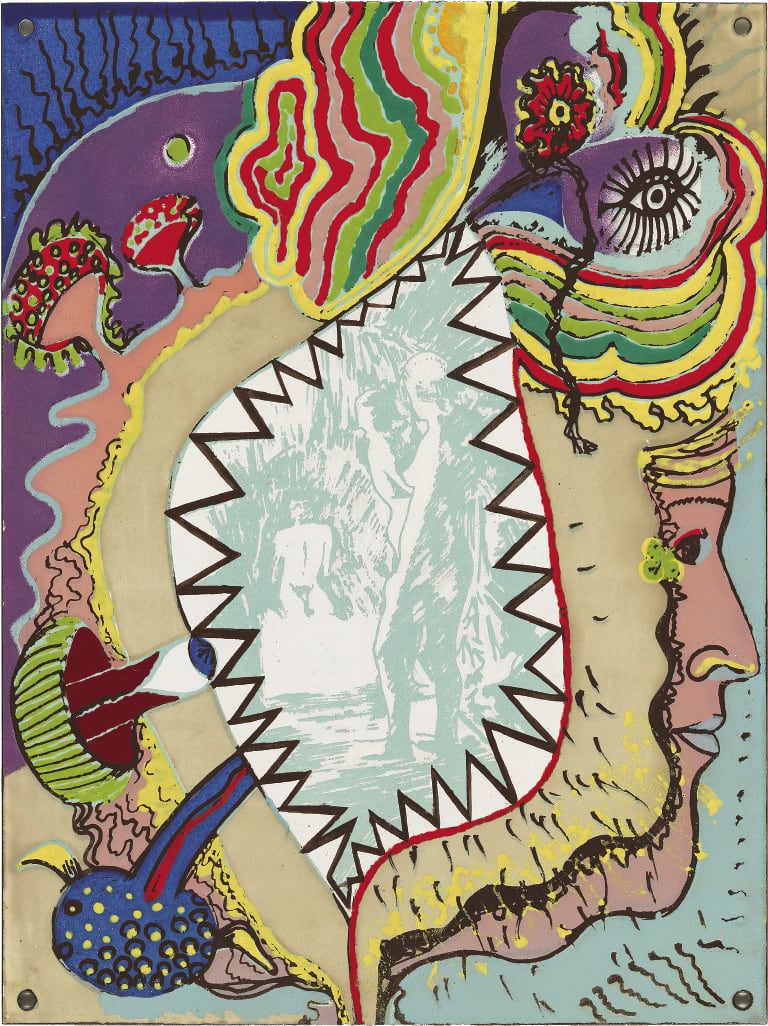

Repro Vag Dens 1975–76 re-presents an image of the collaborative ‘environment’ Woom (with Roger Folley) 1972 framed by a version of the Vag dens (vagina dentata) image famous from Binns’ first solo exhibition in 1967. Much is made of the critical response to Binns’ paintings from that exhibition and of Binns’ subsequent discovery that ‘she could no longer paint’. The imagery for the paintings was developed through a process of automatic drawing, enabling Binns to arrive at images that confronted contemporary aesthetic and social values, particularly in the explicitly sexual imagery of works like Vag Dens. The experience of working in isolation with such psychically intense processes was exhausting in itself, but my feeling is that Binns found playing the traditional role of the artist difficult to reconcile with her own expectations for her practice. Like so many of the works produced by Binns from the mid 1970s onwards, Repro Vag Dens layers images from different sources to create complex narratives. Literally, the progressive, avant-gardist installation emerges from the ‘womb-like’ space of Vag Dens; the work may also be interpreted as Binns reincorporating an abandoned element of her practice within her then-current exploration of creativity and selfhood.

Binns’ early experiments with automatic drawing have their legacy in the artist’s trust for her intuition and process. Binns’ self-reliance led her away from a conventional artistic career toward an engagement with craft and feminist art. This movement away from the aesthetic orientation of the avant-garde tradition was toward an art that aimed for an active engagement with the world and the creation of cultural change. Feminist praxis equipped Binns with skills in collaboration, organisation and research that allowed her to sustain a practice (and income) as a community artist for several years, creating several universally acknowledged community projects. This shift in orientation is something Binns’ practice shares with conceptualism, an art that asks the question about what art is: perceiving art to be a series of connections, contexts and relationships. From one point of view (the view from the academy or the auction house or the museum), the first fifteen years of Binns’ activity as an artist are a series of disparate experiments. From the vantage point of this exhibition, Binns’ early career is a series of sallies at the question conceptual art asks.

One of the ways Binns has approached the question of what art is is to reformulate it continuously throughout her career. Binns approaches the question from different directions: from the point of view of feminism, or as a craftsperson, or by positioning herself at various peripheries of cultural activity. The amateur is one such position — as in the works appropriating photographs taken by her father whilst stationed in Papua New Guinea during World War II, a series represented in this exhibition by the work The vibrant canvas: Unknown NG, phot NAR Binns, NX 19888 1997. Another way to pose the question is ‘why are some things called art and others not?’3 This has obvious relevance to Binns’ appropriation of images from family photo albums, and to her later ongoing series of paintings based on a variety of patterns from found, gifted or appropriated items (In Memory of the Unknown Artist). The materials used in works that explore Australia’s Pacific context are sourced from archival material related to Cook’s explorations of the Pacific, her own snapshots of the ocean surface, and the patterned Tapa cloth from Tonga and surrounding Polynesian islands. Strictly speaking, the marks that adorn Tapa cloth are not solely decoration or pattern but a way of codifying a community’s stories; the cloth itself is traditionally used as currency.4 For Binns, the grid-like patterning used in Tapa evokes the grids that structure the surfaces of much modernist painting, becoming a point of surface contact between Pacific and European-Australian culture. Binns’ attention to the resonances between instances of cultural activity — as currency, ‘work’, ‘research’, information, utopian speculation — marks her practice as a form of poetic enquiry, one that seeks to embody not only the specific intention of the artist but the cultural conditions that presided over the work’s production.

Penny Peckham’s curatorial premise was the perception that Binn’s practice is motivated by the desire to see art as a necessary function of being. The exhibition demonstrates that being human is a state of having culture, connected to the world via a web of social, cultural and political relationships. The role of art is to make these connections material. This philosophic approach to the production of art is most compellingly expressed in works by Binns’ former students, in Geoff Newton’s paintings or in Kate Smith’s relentless examination of aesthetics and politics. Binns depicts being as a complex of shifting layers — as in the tracing of Tapa patterns over images of the ocean at Brisbane Waters or in the interplay of designs in a collaborative work produced with Merryn Gates. The material act of painting is a means to achieving something like the examined life.

Andrew McQualter is a Melbourne-based artist.