What are these films, what outlandish name distinguishes them from the rest? Do they exist? I have no idea as yet, but I do know that there are certain very rare occasions when, without the aide of a single subtitle, the spectator suddenly understands an unknown tongue, takes part in strange ceremonies, wanders in towns or through landscapes he has never seen but which he recognises perfectly…1 — Jean Rouch

Writing on an experience in Paris in the early 1980s, Coco Fusco describes an unwanted sexual advance made towards her by an unnamed ethnographic filmmaker. Fusco recounts being coerced into his car and taken to the filmmaker’s childhood home, a rural plot in an abandoned area, where he commences to mow the lawn in his underwear asking her to collect nuts and berries. At the time, Fusco was an aspiring film graduate meeting to discuss the possibility of work on an upcoming project; she was understandably perturbed by his actions. ‘Deeply immersed in his own fantasy world’, Fusco describes the projection of the man’s imaginary as an excessive incursion into their shared reality with a summary feeling of subjective erasure: ‘What I thought I was, how I saw myself — that was irrelevant.’2 Synoptically, the hazy and indistinct nature of the encounter suggested the fragmentary reality of their initial purpose — cinema.

For Jean Rouch (1917–2004) the correspondence between reality and the cinema was complex. In Rouch’s film Moir, un Noir 1958, set in the Ivory Coast, Oumarou Ganda overdubs a dialogue of detachment from city life in Treichville, a workers’ commune on the outskirts of the colonial capital Abidjan. Along with Eddie Constantine, aka Lemmy Caution, US Federal Agent, Tarzan and Dorothy Lamour, the cut between documentary and myth occurs seamlessly across disparate topologies, collapsing around the arrival of a group of young people at the shores of industrial modernity. Calling himself Edward G Robinson, Ganda narrates: ‘I’m going to dream that one day I’ll be like other men. Like everyone else, like the rich people. I want a wife and a house and a car, like them.’3 As an ethno-fiction, Rouch immediately creates a subjective tension, engendering Robinson on screen while deliberately confusing the boundaries between narrative fiction, reality and performance. ‘The film became a mirror’, Rouch says, introducing Ganda/Robinson, ‘in which he discovered who he was … he is the hero of the film; it is time for me to let him speak.’^4 Rouch’s cinema began as a more specifically ethnographic documentation, working from 1945 at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris throughout an era of de-colonisation in many French West African territories. Rouch’s earlier training in anthropology produced questions of ethnographic documentation and cultural disappearance under the colonial gaze, which was swiftly replaced by his obsession with the transformative potential of the camera. Rouch innately understood the paradox of ethnography, revealed by the scientific attempt at isolating cultural authenticity and lamented by anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski from the outset: ‘the very moment when it begins to put its workshop in order, to forge its proper tools, to start ready for work on its appointed task, the material of its study melts away with hopeless rapidity’.5

The abstract documentation of cultural construction was an impossible task, one Rouch learned quickly to eschew in favour of negotiation, lending his earlier fieldwork — with the Dogon in Mali and the Sorko for In the Land of the Black Magi 1946–47 — a sense of mythologised witnessing across cultures as opposed to detached rational objectivity.6 Rouch narrated in his own words what he perceived first-hand and assembled this into cinema. Inventively dealing with the limitations of early field recording — short film stock, the camera’s weight and size, no synchronisation — his work became a fantastic montage of alterity. The African tribes-people Rouch filmed are mediated by the camera, which became for Rouch his own cultic artefact. To engage with the rituals and ceremonial practices he encountered Rouch developed his own. The camera became the producer of memory images that were then reactivated in the cinema, offering an abject chance to vision outside of a rationalised and scientistic order. Back within the conurbation of the central Western metropolis, Rouch effected an inversion that disrupted the safe distance the cinema often represented, revealing persistent superstitions and dislodging the comfortable binary of otherness.

A strange dialogue takes place in which the film’s ‘truth’ rejoins its mythic representation.7

‘The aesthetic quality of the visuals’, Rouch wrote, ‘were of little importance’, and his tenacious style of cinema vérité, following the pioneering techniques of Dziga Vertov’s cine-eye, produced images that haunted the subjects of his films and manipulated the trajectories of their realities through the technical imposition of the camera.8 In many ways Rouch’s feedback method of recording and re-filming the subjects reacting to their on-screen personas revealed the performance of life on film, blurring the distinctions between the everyday and the act of cinema. The camera was for Rouch a magical apparatus that could induce trance-state inebriations and carry clandestine images between disparate communities. In the forgetting of one’s persona, the disorienting reproduction of the image becomes ‘the “film-trance” (ciné-transe) of the one filming the “real trance” of the other’.9

Photographic reproduction, science’s analogical pursuit of reality, has a specific characteristic that informs the gesture of those under the camera’s gaze without specific coercion. The authority in question is the temporal index of the gesture that becomes an evolutionary language within a documented historical origin. German scholar Aby Warburg similarly eschewed what he called ‘aesthetisising art history’, the reductive discipline of ‘the formal contemplation of images’ in favour of a cultural methodology that posed an ontological theory of the image in motion concurrently with its technical deployment by the camera.10 Warburg’s ‘Memory Atlas of Images’ (Bilderatlas Mnemosyne) approached the reproduction of gesture through the concept of pathetic formulas (Pathosformeln) that revealed a cultural crystalisation in moments of empathic rhetorical transmission. The orientation of a culture through the reproduction of its images depended on what Warburg called an ‘oscillation of causation’, as the images became signs.11 This technical procedure of memorial transmissions was revealed to Warburg not by studying Western epistemology but through particularly fertile encounters with cultural difference. Among the Hopi Indians in the late nineteenth century Warburg connected the images of a culture to movement in a way that can only begin to be suggested by the cinema’s capitalisation of perceptual illusion. The still image moves, crystallised by memory, through an active encounter with its cultural value. Rouch’s ciné-transe, as an activating technique that approaches the image through the camera, is revealed in Warburg’s proposal of movement interrupting the linear flow of time sequentially reconstructed by the film frame. This oscillation is exposed through a distance that positions orientation from the horizon of perception as a set of cultural constructions that Rouch could exploit when he turned the camera back on the blind-spot of vision, the fictional subject at the centre of the cinema apparatus.

Images do not exist in nature, they exist only in the mind’s eye and in memory.12

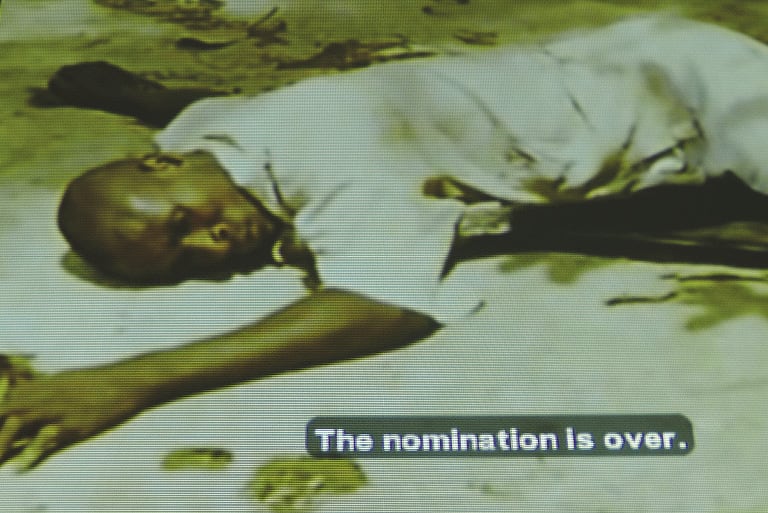

For Edgar Morin, Rouch’s collaborator on Chronique d’un été (Chronicle of a Summer) 1960, and an anthropologist whose adherence to the cultural value of images cannot be overstated, cinema ‘allows us to see the process of the penetration of man in the world and the inseparable process of the penetration of the world in man’.13 This collision exposes the Parisian streets to a renewed image of its internal mechanisms as it interrupts the flow of the modern city, imposing itself in the routinised spaces it produces. The externalisation of the memory’s image through the technical apparatus of the camera suggests for the question of orientation that had so concerned Warburg earlier in the century. The auteurs of the French New Wave were also taken by Rouch’s ability to interrupt the everyday, producing a slice of dialectical tension utilising the camera’s montage incursions.14 After providing ‘walking’ sequences of the public traffic with Parisians answering the question posed: ‘Are you happy?’ Rouch provokes a climactic encounter between two African-French émigrés and a French holocaust survivor whose tattooed arm carries no meaning to the men. The registering of shock and the trauma of this revelation exceeds the playful structure of the film to the observer, much like the images of possessed Hauka mimicking their oppressors and frothing from the mouth in Rouch’s earlier, and most scandalous film Le Maîtres Fous (The Mad Masters) 1955.15 When the camera is manoeuvred into a space for imagistic conflict, the empathic effect of these gestures register on the viewer, embedded within the transfer of the image. As a technical apparatus the cinema does not only reproduce, but also produces, these images outside of their contingent historical collaboration.

Gilles Deleuze, writing on Rouch, concluded: ‘As a general rule, third world cinema has this aim: through trance or crisis, to constitute an assemblage which brings real parties together, in order to make them produce collective utterances as the prefiguration of the people who are missing.’16 The third world here is the imaginary, the world of images, a perceptual imperative that effaces constructed differences and suggests the gestural potential for communication. Rouch’s resistance to the structuralist milieu produces a cinema where ‘experiences of every kind and condition which, more or less at the mercy of indefinable circumstances, may become films running twenty minutes or five hours, which may or may not reach the screen’, and may no longer require the presence of a camera.17 Rouch’s cinema suggests a theatricality of the gesture that opens the entire world to experience.

By participating, the observer betrays the filmmaker’s own experience of the film, an intermediation which, maintaining the internal prerogative of the imagination, orients the film in a particular relationship to the image. The question of the camera’s role within this practice (Rouch worked closely with the development of the film-camera throughout his life) suggests a particular collaboration between labour and memory, reproduction and the image. Filmmakers today who share this concern produce films that use the cinema not so much to remove the spectator from reality, as to re-orient them through the projection of the cinema’s figures from outside of their historical temporalities. What Rouch discovered was an affinity between the technical and the human, as it concerned memory. By introducing an anti-subjective adhesion that attempted to erase constructed colonial boundaries in order to reach for a simpler sense of being, Rouch constantly provoked the fictions of reality — even those revealed in the simple act of cutting the grass.

Giles Fielke is a writer interested in thinkable gaps and thematising failures, particularly between the image and language.