1

It is in the social that painting finds criticality. Painting’s particular set of constraints, its two-dimensionality, its ‘faciality’, its frontal, pictorial flatness, do not detract from this function. Painting by its nature sits apart. In this way it is predisposed to make comment. At the recent Paul Taylor symposium,1 someone — I think it was Adrian Martin — talked about how Paul, in his general approach to life, chose to take on the character of the person who comes to the dinner party and manages to offend everybody at the table. Perhaps this can also be a model for painting — painting frustrates sculptors with its insistent two-dimensionality, with its own idea of temporality, whilst still making use of narrative. It can be illustrative, decorative. Dirty words, frowned upon for being too saleable, in spite of this being an outmoded criticism considered in light of the public commission, the editioned video, the artist in general as a funnel for institutional spending, and so forth. So painting gets to keep its stigma and be the emblem of everything that’s wrong with art.

2

Paintings, in the more traditional sense, are not by their material nature participatory. You stand back from them, you are not supposed to touch their surface, or even get too close. The painter in the studio at times advancing to work on the surface, then retreating a few steps to see how it will read from a point of removal. Coding distance into the painting’s materiality.

3

As an object to be judged critically, painting, like any form, can function as a site for the emergence of subjective universality, arising from aesthetic reflection. The viewer pits her judgement against an array of possible opinions distributed across an imagined society. This abstracted perception of society is one in which the viewer has a personal stake, and is responsible for, arising as it does in her own mind. Inclusivity as a strategy sits in opposition to this, taking its place on the other side, along with ‘likes’, ‘shares’ and ‘retweets’ in its approach to consensus. Why is the Internet such a hostile ground for opinion, so much of the time? Partly, I would argue, because it acts to erode subjective universality in favour of a different kind of consensus, producing a universal community in which a sense of personal responsibility towards the whole is not inbuilt. When it comes to the question of the virtual universal, we seem to find ourselves in the realm of neoliberalism, the open market and personal productivity. The sense of responsibility towards a notion of society is replaced with responsibility for the crafting of one’s own virtual presence, and the virtual representation of real-world communities — subjectivity and universality are separated out from one another.

4

The question of what can actually be termed ‘the social’ now. The social is in a state of flux, shifting from subjective universality to abstract individualism, from Kant’s idea of society to Hegel’s.

5

A woman at the Art Gallery of New South Wales thumbs her iPhone, absorbed, as her small daughter runs her sticky fingers across the bottom of a Nolan. We laugh.

6

Painting, actually making a painting, is in my experience, from the outset, a deeply antisocial practice. When I am painting, the studio functions as an extension of my mind, and I am not keen to have anyone in there while it is functioning in this mode. Radio National spills out information, this week about permeate in milk, leftist Russian billionaires from the seventies, the horrors of the Australian meat industry and the latest political gaffes.

7

When stretching a canvas, you make friends with it, you owe it something, and it owes you. A crowd of them, hanging around the studio, having visual conversations. At times I stick memos on them to remind me of turning points, elements of content that might come later. The white knight. An EFTPOS machine. Old school chums. Centrelink.

8

Sitting at dinner listening to Tim Johnson talking about how his little twin boys are afraid of UFOs. Telling stories of UFO sightings, and ghost stories. Really scary ones. Local ones. Stories from the desert in America, and from the desert here. Tim, up in the desert, finding a huge painting folded and stuffed behind a washing machine. This story keeps folding out.

9

The best discussion I saw at this year’s AAANZ Conference: Una Rey and Ian McLean talking about Michael Jagamara Nelson’s collaborations with Tim Johnson. The difficulty, the awkwardness they both felt, and the way that for a long time they both protected their territory within a given painting, but over time found ways to make it work more as a collaboration. The difficulty of navigating this approach in a space between Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures in Australia.

10

Kerstin Brätsch talks about the flexibility and interchangeability of her paintings as though this imbues them with criticality. To my mind the modularity makes them more a marriage of post-conceptual painting with modernist furniture, or with the pop-up store. Apparently Brätsch ‘puts notions of artistic genius and authenticity to the test.’2 In her view, circulation and flexibility are posited against commercialisation as though they can be a form of resistance to it, which is something akin to positing the oar against the boat. In the Summer 2011 issue of Mousse magazine, Brätsch and Amy Sillman interview one another about their respective painting practices. Both are women producing huge, bold paintings. They seem to dislike each other, the interview is passive-aggressive in tone. They undercut one another’s positions throughout, a bit like politicians. Still, in this context, it is better than mutual backslapping.

… I’m just saying when painting, there is an awareness of how things have been used and maybe an attempt to find a new usage of the tools in ‘painting’ and ‘the painter’. The painter, the figure ‘Brätsch’, how I use the painter in quotes within the way I work and the scale I’m using, it’s definitely a reference to the history of German painting.

Yes it’s true, I enjoy occupying this territory where I feel like I’m an imposter, and I’m also kind of proud of using a ‘male’ scale, so to speak. It’s a form of drag for me.

OOH-la-la!3

11

In the same issue of Mousse, Lucy McKenzie and Marc Camille Chaimowicz hold a lengthy conversation, with Michael Bracewell as facilitator.4 McKenzie and Chaimowicz are more on the backslapping side of things but they are so erudite and assured that the reading is entertaining.

michael bracewellAt the Tate a few years ago you showed this really confrontational painting. Can you tell me about that painting and how you came to make it?

lucy mckenzieThat painting was inspired by the experience of being in an institution called the DESTE Foundation in Athens. I traveled as a friend of some artists who were showing in the city and we were all invited for a fancy dinner there. The dining room was decorated with the Jeff Koons Made in Heaven series, so we had to sit and eat under these images. Over the years I’ve been in several places like that, with Araki photographs or whatever hanging. I wanted to make a painting that expressed the banal fatigue I feel when this kind of art is used as décor, when we’re expected to just accept pornography as a scenic prop in the art world.

Bracewell goes on to declare that the painting McKenzie made in response is ‘infinitely more shocking work than anything Koons has come up with’.5 I have always thought it quite a nice painting. It shows a woman, bored, chin in hand at a dining room table in an opulently decorated room. Above her hangs a painting of a woman kneeling, ‘ass north’ as Lil Wayne would say, fingering herself as she holds a terse conversation with her girlfriend. I had interpreted this scene as suggesting that the woman at the table was bored of her meal, ‘meat and three veg’, and that the masturbation fantasy was the space she would prefer to inhabit. I don’t find it shocking. Is the subtext of the conversation that painting can still be more shocking than photography, or is it more about Bracewell wanting to flatter McKenzie?

12

One of Richard Bell’s paintings was hanging at the Art Gallery of New South Wales a couple of months ago, downstairs to your left as you came down the escalator. The painting says in big white letters ‘Pay the Rent’. They were holding some kind of members’ event in front of it. Ladies who lunch, nibbling on pastries in a cordoned off area, just the ladies and the painting inside.

13

After an opening one night in 2008, Richard and I pashed, and everyone else split the scene. We didn’t care. The week prior, I pashed Kate Smith in the back of a taxi. Those were the days.

14

An image of Charline von Heyl and Christopher Wool, taken by Aubrey Mayer. Two painters, husband and wife. She is at the forefront of the new abstract mode. He the post-conceptualist, moving beyond theoretical readings. Von Heyl is in the foreground, eyes softer than usual and a small cock in one eyebrow. He, slightly behind, peering at the lens from beneath his woolly brows. A suggestion of a grin. Both a little lopsided. Is it the lens, or have they both had broken noses? He has shades of Picasso. She is aging with grace.

15

I’ve painted a lot of people I know. I did a lot of paintings of a previous boyfriend when we were together, which was a period of about eight years. We haven’t spoken much since we broke up. One of these paintings went up for auction earlier this year. Some people I know bought it, and now they have a painting of my ex-boyfriend that hangs next to their bed. The storing of memories in other people’s houses. People laugh, speculating that this stuff will be written into the history later. Social underpinnings — this doesn’t really get spoken about as part of the work, at the time of its making, and it is not always even evident until things change. I bet the artists who lived at Heide never imagined how many future wall didactics in the place would offer tidbits about the grimy social milieu within which their painting practices nestled. It’s not to suggest that people weren’t aware of this as an aspect of art production, but perhaps our ability to speculate on it reflects the post-Fordist context in which everything is up for grabs in the service of the commodity, the tacit agreement not to air one’s dirty laundry is not such an easy fit with the logic of the market.

16

Jutta Koether stalking and gesturing around her sketchy remake of Poussin’s Pyramus and Thisbe 1651. The painting is rendered in sore-looking reds and purples. It is lit with a huge spot salvaged from The Saint, a famous gay nightclub in New York that closed in the late eighties.6 Anachronism on anachronism. Koether, dressed from head to toe in red velvet, in clompy red heels, lies down as she says: ‘a woman whose goal it is not to be walking on the red carpet, but to initiate to become a red carpet’.7 The painting is hung on a free-standing wall with one foot in and one foot out of the gallery, as though it is trying to sneak away.

17

Julia Gorman’s blog. She is going through and scanning slides of a lot of old work, and talking about what she was thinking and feeling about the work when she made it, and what she thinks and feels about it now. Reading it makes me want to hotfoot it to the studio and paint. It is friendly, sardonic and funny. In the post ‘Paintings 1997’, she writes ‘Ideally I’d be like Brice Marden, with a summer studio in the Greek Islands. He paints in the morning, then has lunch, he rides his horses, and/or goes for a swim. His paintings dry quickly in the heat, so he comes back and does a bit more on them in the late afternoon.’8

18

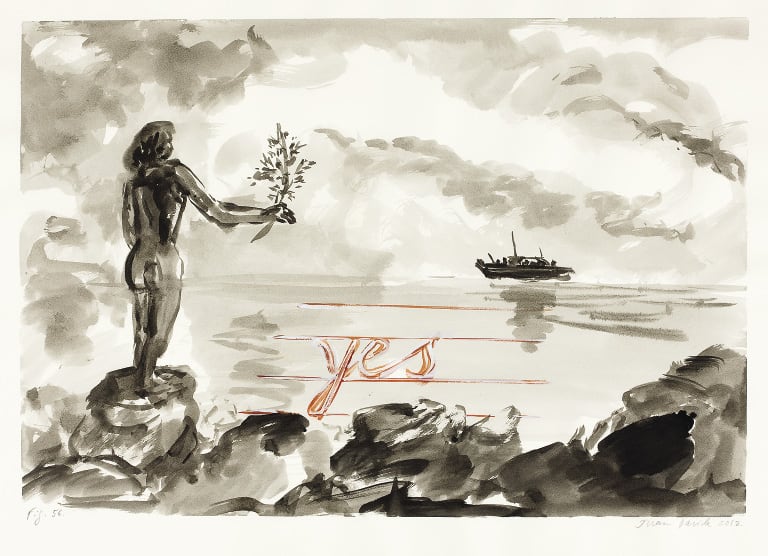

Juan Davila’s exhibition at Ormond Hall in August 2012 contained a small painting, ink on paper, one of many. Loosely painted, it showed a person gazing out to sea, holding a small branch. An olive branch? Eucalyptus? The person is naked. A woman or a man? It is unclear. What is their nationality? Also unclear. There is a boat on the horizon. It might be a boatload of asylum seekers, or it might be a tall ship with its sails furled. Masts or aerials. In red across the scene is written ‘yes’ in classroom cursive. An image constituted of ambiguities. The situation is so very fraught. Imagine if an image like this were to take up the front page of an Australian newspaper one day? It might incite meaningful debate.

Helen Johnson is an artist and a writer.